[sharelines]New transit villages focus on the private sector, value-added transit, and implementation.

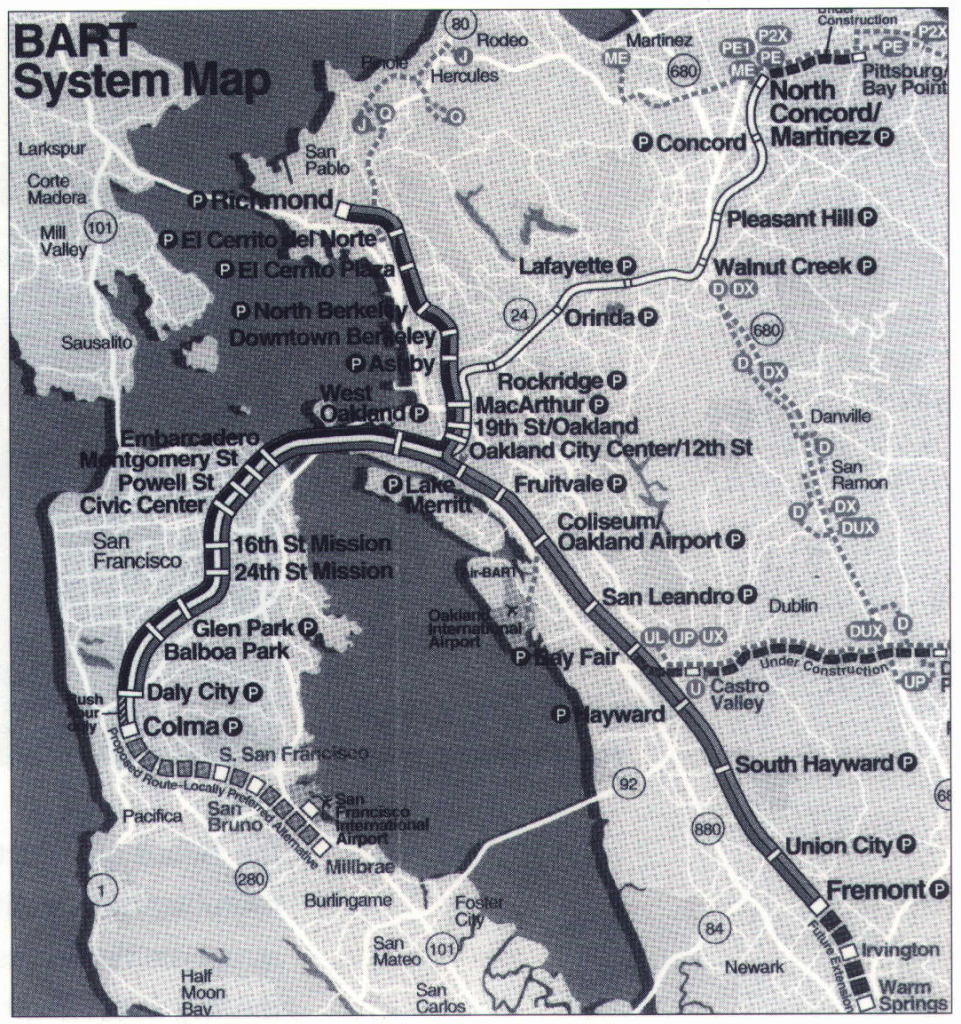

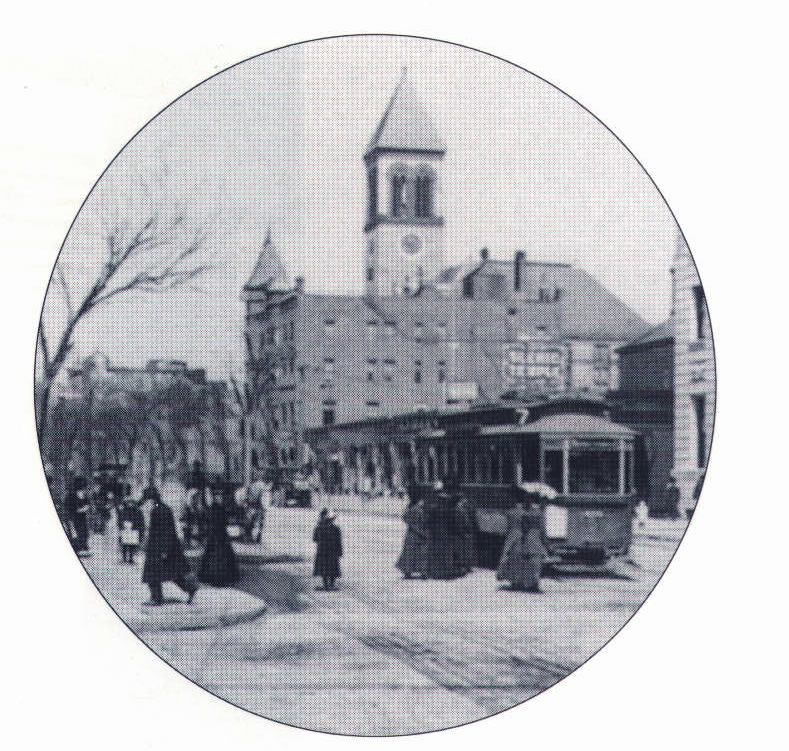

The Bay Area Rapid Transit system (BART) helped pioneer the development of metropolitan rail transit around the country. But did it accomplish all original goals? The initial 1956 plan primarily aimed to save old city centers and reorganize sprawling suburbs by inducing subcenters there. Spaced about 2.5 miles apart, station stops were to become points of high accessibility that would attract high-density residences, retail shops, and office employers. By reshaping the land market through transit-induced access, BART’s planners sought to reshape the metropolis and to eliminate traffic congestion.

It’s now been twenty-four years since BART began carrying passengers. Downtown San Francisco has been expanding, no doubt nurtured by four busy stations under Market Street; and downtown Oakland has held its own, with two subway stations at the system’s transept. But the suburbs and urban areas outside central business districts have not changed very much. Despite huge public investment in enhanced accessibility at specific suburban station sites, improvements have been minimal. And traffic congestion remains as troublesome as before.

Part of the reason for suburban recalcitrance lies in the highlevel of accessibility provided by the auto-highway system. BART’s added access represents only a small proportional addition, even where congestion is severe. The linear geometry of the rail lines means that few origins and destinations are near stations, so most people continue to use autos. Several local neighborhood groups opposed multi-family housing near stations. Aggressive governmental programs were absent in most towns along the lines. Equally important, BART managers saw themselves as railroad people, not land developers, and thus did little to encourage private-sector construction near stations.

Until recent years, BART officers focused on getting the railroad to run on time. Now that the machinery is working well, the Board of Directors and staff are turning their attention to the neighborhoods surrounding rail-transit stations. They have already successfully encouraged builders to construct medium-density housing at some stations. Now they are seeking to use BART as the key instrument for redeveloping a deteriorating inner-city station site by creating a viable transit village there.

The Fruitvale Transit Village

BARTs routes radiate out from the city centers in San Francisco and Oakland through inner-city districts that are experiencing the familiar patterns of demographic change and physical deterioration. En route to the suburban stations between San Leandro and Fremont, BART runs through East Oakland’s older neighborhoods, including Fruitvale, with its ethnically diverse population, many with low incomes.

Ever since the area was settled over a hundred years ago, East Oakland’s main transport and retail corridor has been East 14th Street. During the 1950s and even up through the 1960s its junction with the Fruitvale Avenue was the site of a vibrant commercial center. It was therefore a natural choice for a BART station stop.

However, in a classic case of urban economic decline, East Bay malls then opened in suburban San Leandro and Hayward and drew consumers away from East 14th Street and the Fruitvale center. Various anti-poverty plans were devised to revitalize the area, with no serious results. As Clyde Brewer, a Fruitvale store owner for eighteen years, recently stated, ”You and I and twenty of our friends could retire on the money that has been spent studying this area – with no visible effect.”

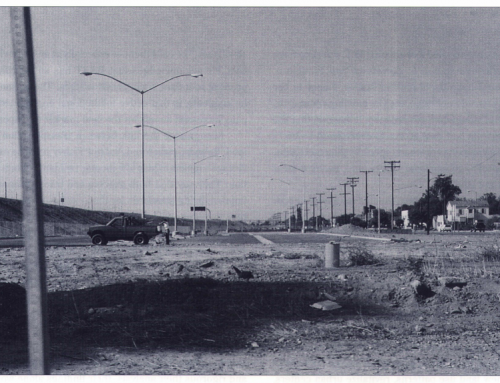

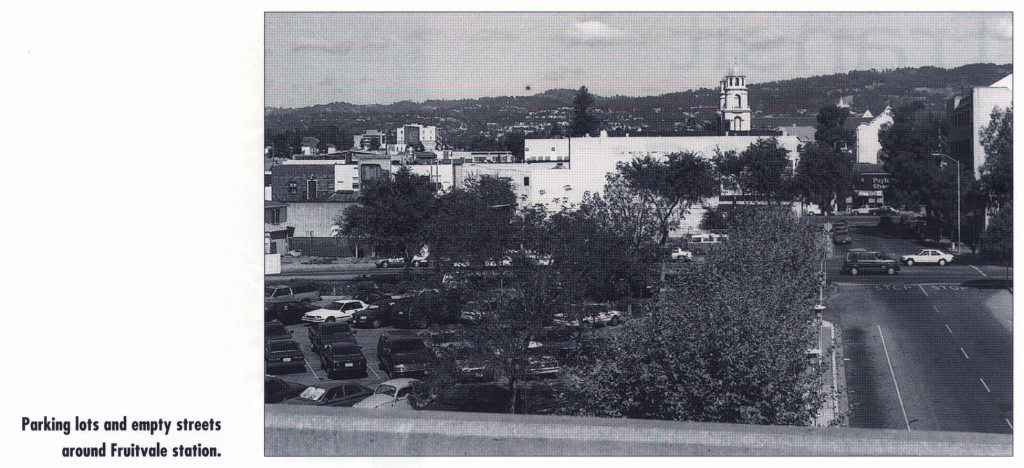

By 1993, the Fruitvale station area had become a series of parking lots and dilapidated buildings. The BART station is immediately surrounded by two surface parking lots. Most of the view from the station toward East 14th Street displays the backs of buildings. Nearby on East 14th Street, there are two discount shoe stores, a Mexican fast-food restaurant, a discount furniture store, and several empty storefronts.

In 1991 the Spanish-Speaking Unity Council (SSUC), a local community group headed by a former HUD official, Arabella Martinez, called for a neighborhood revitalization effort. Using Fruitvale’s main asset, the nearby BART station, as their primary tool, they sought to spur new development. To jump-start the process, they staged a design symposium.  Five prominent Bay Area architectural firms volunteered to collaborate with local residents in preparing and presenting different concepts for station-area improvement.

Five prominent Bay Area architectural firms volunteered to collaborate with local residents in preparing and presenting different concepts for station-area improvement.

They jointly concluded that conditions commonly viewed as liabilities – sterile parking lots, dilapidated buildings, vacant parcels – can over time be turned into economic assets. They debated whether housing should be concentrated in one sector or spread throughout the area. They considered whether parking should be placed between BART and East 14th Street as inducement to shopping along the commercial street. They devoted much attention to finding ways of rebuilding the business base of East 14th Street and the immediate station area.

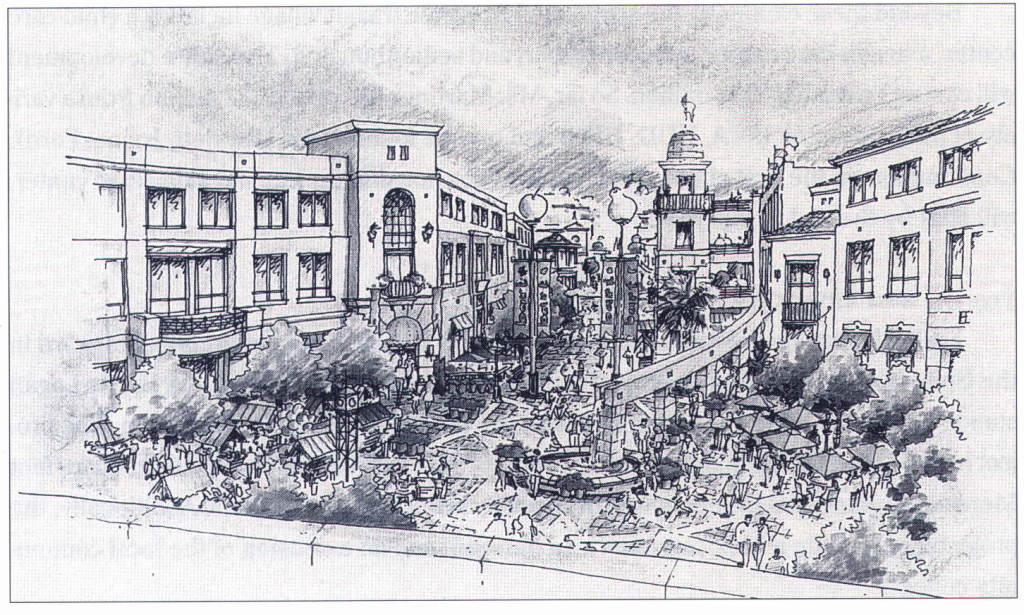

The Council then engaged Ernesto Vasquez of the Costa Mesa-based firm of McLarand-Vasquez as site designer. During the next two years Vasquez met with the stakeholders: existing business owners on nearby East 14th Street, Fruitvale residents, and officials from BART and the city of Oakland, the two largest landowners in the area. Their collaboration has produced a transit-village plan that pursues several social goals, including promoting local entrepreneurship, employment of local residents, greater home-ownership, and increased BART patronage.

Housing will be the main component of the transit village. More than 500 units will be built in the area, primarily as second and third floor flats above shops. The spatial distribution of housing should create a 24-hour presence, avoiding an empty plaza after business hours.

Small shops in an open-air mercado will bring both commuters and local residents to the shopping center, marked by a Hispanic theme.

Cultural and entertainment elements, including a Mexican Museum and a LatinArnerican library, will attract Hispanic residents and encourage multiethnic participation.

Open space, a public plaza, and a walkway lined with palm trees along East 14th Street will provide a venue for public events.

Public safety will be assured by encouraging “eyes on the street” and by locating a police station within the transit village.

Beyond these elements, the envisioned Fruitvale transit village includes a child-care center, a health-care center, a senior center, and senior housing. The entire development will cost an estimated $100 million. So far, Ms. Martinez has raised $23 million from a variety of public sources (FTA, HUD, HHS) and private foundations (Hewlett, Irvine, Ford). Construction on the first phase, the 68-unit senior-housing project and a day-care center, will start by the end of this year.

Transit and Inner City Revitalization

Fruitvale may be the most extensive inner-city transit-village effort going forward in the United States, but another project is underway in San Diego. There, the Barrio Logan station has become the site of a mixed-land-use project centered on the station. The project includes the Mercado Apartments, 144 units built in 1992, and the 100,000 square foot Mercado Commercial Center, a mix of specialty retail and vendor carts. Additionally, the project may include a Mexican-American museum and an extension of the local community college.

These transit-village efforts differ from previous anti-poverty and land redevelopment efforts in essentially three ways:

- Emphasis on the Private Sector

Contemporary ideas for transit villages represent an intellectual and policy departure from the traditional concept that viewed government as landlord/ owner/employer in inner cities. Through the 1960s and the 1970s, public policy treated declining innercity areas with massive urban renewal under the stewardship and control of public agencies. Wide swaths of established neighborhoods were bulldozed and replaced by highrise public housing. Social service agencies replaced local businesses as employers, and urban renewal programs themselves became major sources of jobs.

The transit village stands in contrast to that big-government approach. Village-size in scale, it relies on local entrepreneurs and the skills and abilities of local residents. At Fruitvale, the redevelopment project is limited to the quarter-mile ring around the station. The transit village is being designed for households having varied incomes and backgrounds, not just the poor. Public money is being used to leverage private investment. Fruitvale area residents are not passive observers, but direct participants in village development and business ownership.

There remains an important first-stage financing role for government, however. A critical mass of new housing and public infrastructure (plaza, police station) is needed before the Fruitvale project will attract very much private capital – and this financing is coming from public-sector sources. However, the goal is a community in which ownership of businesses, housing, and civic establishments is in private hands, and most jobs are with private employers.

- Value-added of Transit

Transit-village elements noted above – local scale, mixes of incomes and land uses, pedestrian orientation – all are elements of the “urban village” movement of the 1980s. Yet, it is the transit link that makes the transit village more economically viable than most urban village designs.

The retail elements benefit from the thousands of daily commuters coming to and from the station. The office and other commercial elements benefit from the additional mobility option offered by the transit link-a benefit proportional to the degree of regional traffic congestion. Both the retail and commercial elements are further strengthened by the civic spaces and increased public safety of the transit village.

Of course, the transit link is not sufficient to guarantee private-sector growth. It only encourages private-sector efforts and increases the potential for new urban growth.

- Implementation

Development at Fruitvale differs from that at other BART stations by having strong sponsors within both the BART Board of Directors and the local community. Twenty odd years ago, planners expected that the market would respond spontaneously to the added accessibility brought by BART’s arrival. But we now know that’s not enough. If subcenters are to emerge at rapid-transit stations they will be the product of concerted entrepreneurship.

To be sure, they will also rely on the active participation of the transit agencies and local governments, as well as federal recognition in Section 3 “rail-start decisions.” These revised federal criteria give increased emphasis to land use planning in federal transit funding. Previously, land use was a low priority among other funding criteria and cost ratios, but under the new criteria issued this year, station area planning is given prominence. This change, combined with FTA’s Livable Communities Initiative, will be important in supporting local efforts.

Emerging transit-based development in the US (for example, Pleasant Hill near San Francisco and Ballston near Washington, DC) are demonstrating the importance of transit-agency leadership. Each of these started with a market-based site and phasing plan for a quarter-mile  radius. Each required proactive measures in land assembly, infrastructure investment, shared parking, expedited permits and reviews, write-down of land costs/lease payments (in return for project revenue participation), and direct financial participation (issuance of tax-exempt bonds, loan guarantees, equity participation) .

radius. Each required proactive measures in land assembly, infrastructure investment, shared parking, expedited permits and reviews, write-down of land costs/lease payments (in return for project revenue participation), and direct financial participation (issuance of tax-exempt bonds, loan guarantees, equity participation) .

Additionally, each has shown the importance of a project champion – an elected or appointed official or a neighborhood activist – who persists in pushing the project and keeping it on course amidst inevitable obstacles and delays. Fruitvale has Ms. Arabella Martinez, who has assumed this role for six years. At the Pleasant Hill BART station area, a local county supervisor, Ms. Sunne McPeak, pushed the project for fourteen years, from initial planning to the current state of 60 percent build-out.

At BART headquarters, a transit-based development program is now firmly established. A Joint Development Subcommittee of the Board of Directors oversees station-area efforts, and several board members are involved in individual station-area plans. A three-person staff negotiates with private developers and with local municipalities, both for development on BART-owned land and on the surrounding land one-quarter mile around the station. Direct revenue to BART is only a secondary goal. Increased ridership, station-area security, and station-area attractiveness are among the primary goals.

The transit-village concept has become an organizing principle, not only for regional transportation but also for community development. By linking inner-city transit services with community-development efforts, both gain in the uphill battle to restore inner-city areas.

Further Reading

Michael Bernick and Robert Cervero, Transit Villages for the 21st Century (New York: McGraw Hill, 1996).

Michael Bernick, Urban Illusions (New York: Praeger Press, 198 7).

Robert Cervero, ” Transit Villages: From Idea to Implementation,” ACCESS No. 5, Fall 1994.

Robert Cervero, “Transit-Based Housing In California: Evidence on Ridership Impacts,” Transport Policy, Vol. 1, 1994.

Witold Rybczynski, City Life: Urban Expectations in a New World (New York: Scribner, 1996).