Rethinking Traffic Congestion

Brian D. Taylor

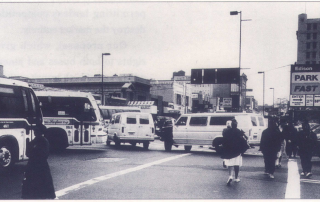

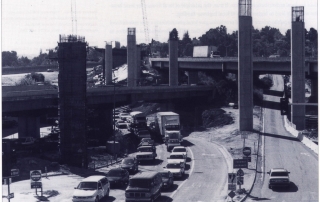

Traffic congestion and cities, it seems, go hand in hand. Everyone complains about being stuck in traffic; but, like the weather, no one seems to do anything about it. In particular, traffic engineers, transportation planners, and public officials responsible for metropolitan transportation systems are frequently criticized for failing to make a dent in congestion.

But is traffic congestion a sign of failure? Long queues at restaurants or theater box offices are seen as signs of success. Should transportation systems be viewed any differently? I think we should recognize that traffic congestion is an inevitable by-product of vibrant, successful cities, and view the “congestion problem” in a different light.