The money you put into a parking meter seems to vanish into thin air. No one knows where the money goes, and everyone would rather park free, so politicians find it easier to require ample off-street parking than to charge market prices at meters. But if each neighborhood could keep all the parking revenue it generates, a powerful new constituency would emerge—neighborhoods that receive the revenue. Cities can change the politics of parking if they earmark parking revenue for public improvements in the metered neighborhoods.

The money you put into a parking meter seems to vanish into thin air. No one knows where the money goes, and everyone would rather park free, so politicians find it easier to require ample off-street parking than to charge market prices at meters. But if each neighborhood could keep all the parking revenue it generates, a powerful new constituency would emerge—neighborhoods that receive the revenue. Cities can change the politics of parking if they earmark parking revenue for public improvements in the metered neighborhoods.

Consider an older business district where few stores have off-street parking, and vacant curb spaces are hard to find. Cruising for curb parking congests the streets, and everyone complains about a parking shortage. Parking meters would create a few curb vacancies, and these vacancies would attract customers willing to pay for parking if they don’t have to spend time hunting for it. Nevertheless, merchants fear that charging for parking would keep some customers away. Suppose in this case the city promises to use all the district’s meter revenue to pay for public amenities that can attract customers, such as cleaning the sidewalks, planting street trees, putting overhead utility wires underground, improving store facades, and ensuring security. Using curb parking revenue to improve the metered area can therefore create a strong local interest in charging the right price for curb parking.

Right Prices

The right price for curb parking is the lowest price that keeps a few spaces available to allow convenient access. If no curb spaces are available, reducing their price cannot attract more customers, just as reducing the price of anything else in short supply cannot increase its sales. A below-market price for curb parking simply leads to cruising and congestion. The goal of pricing is to produce a few vacant spaces so that drivers can find places to park near their destinations. Having a few parking spaces vacant is like having inventory in a store, and everyone understands that customers avoid stores that never have what they want in stock. The city should reduce the price of curb parking if there are too many vacancies (the inventory is excessive), and increase it if there are too few (the shelves are bare).

The right price for curb parking is the lowest price that keeps a few spaces available to allow convenient access. If no curb spaces are available, reducing their price cannot attract more customers, just as reducing the price of anything else in short supply cannot increase its sales. A below-market price for curb parking simply leads to cruising and congestion. The goal of pricing is to produce a few vacant spaces so that drivers can find places to park near their destinations. Having a few parking spaces vacant is like having inventory in a store, and everyone understands that customers avoid stores that never have what they want in stock. The city should reduce the price of curb parking if there are too many vacancies (the inventory is excessive), and increase it if there are too few (the shelves are bare).

Underpricing curb parking cannot increase the number of cars parked at the curb because it cannot increase the number of spaces available. What underpricing can do, however, and what it does do, is create a parking shortage that keeps potential customers away. If it takes only five minutes to drive somewhere else, why spend fifteen cruising for parking? Short-term parkers are less sensitive to the price of parking than to the time it takes to find a vacant space. Therefore, charging enough to create a few curb vacancies can attract customers who would rather pay for parking than not be able to find it. And spending the meter revenue for public improvements can attract even more customers.

We can examine the effects of this charge-and-spend policy because Pasadena, California, charges market prices for curb parking and returns all of the meter revenue to the business districts that generate it. An evaluation of Pasadena’s program shows it can help revitalize older business districts by improving their parking, transportation, and public infrastructure.

Old Pasadena

Pasadena’s downtown declined between 1930 and 1980, but it has since been revived as “Old Pasadena,” one of Southern California’s most popular shopping and entertainment destinations. Dedicating parking meter revenue to finance public improvements in the area has played a major part in this revival.

Old Pasadena was the original commercial core of the city, and in the early 20th century it was an elegant shopping district. In 1929, Pasadena widened its main thoroughfare, Colorado Boulevard, by 28 feet, and this required moving the building facades on each side of the street back 14 feet. Owners removed the front 14 feet of their buildings, and most constructed new facades in the popular Spanish Colonial Revival or Art Deco styles. However, a few owners put back the original facades (an early example of historic preservation). The result is a handsome circa-1929 streetscape that is now the center of Old Pasadena.

Old Pasadena was the original commercial core of the city, and in the early 20th century it was an elegant shopping district. In 1929, Pasadena widened its main thoroughfare, Colorado Boulevard, by 28 feet, and this required moving the building facades on each side of the street back 14 feet. Owners removed the front 14 feet of their buildings, and most constructed new facades in the popular Spanish Colonial Revival or Art Deco styles. However, a few owners put back the original facades (an early example of historic preservation). The result is a handsome circa-1929 streetscape that is now the center of Old Pasadena.

The area sank into decline during the Depression. After the war the narrow storefronts and lack of parking led many merchants to seek larger retail spaces in more modern surroundings. Old Pasadena became the city’s Skid Row, and by the 1970s much of it was slated for redevelopment. Pasadena’s Redevelopment Agency demolished three historic blocks on Colorado Boulevard to make way for Plaza Pasadena, an enclosed mall with ample free parking whose construction the city assisted with $41 million in public subsidies. New buildings clad in then-fashionable black glass replaced other historic properties. The resulting “Corporate Pasadena” horrified many citizens, so the city reconsidered its plans for the area. The Plan for Old Pasadena, published in 1978, asserted “if the area can be revitalized, building on its special character, it will be unique to the region.” In 1983, Old Pasadena was listed in the National Register of Historic Places. However, despite these planning efforts, commercial revival was slow to come, in part because lack of public investment and the parking shortage were intractable obstacles.

Parking Meters And Revenue Return

Pasadena devised a creative parking policy that has contributed greatly to Old Pasadena’s revival: it uses Old Pasadena’s parking meter revenue ($1.2 million in 2001) to finance additional public spending in the area.

Old Pasadena had no parking meters until 1993, and curb parking was restricted only by a two-hour time limit. Customers had difficulty finding places to park because employees took up the most convenient curb spaces, and moved their cars every two hours to avoid citations. The city’s staff proposed installing meters to regulate curb parking, but the merchants and property owners opposed the idea. They feared that paid parking would discourage people from coming to the area at all. Customers and tenants, they assumed, would simply go to shopping centers like Plaza Pasadena that offered free parking. Meter proponents countered that employees rather than customers occupied many curb spaces, and making these spaces available for short-term parking would attract more customers. Any customers who left because they couldn’t park free would also make room for others who were willing to pay if they could find a space, and who would probably spend more money in Old Pasadena if they could find a space.

Old Pasadena had no parking meters until 1993, and curb parking was restricted only by a two-hour time limit. Customers had difficulty finding places to park because employees took up the most convenient curb spaces, and moved their cars every two hours to avoid citations. The city’s staff proposed installing meters to regulate curb parking, but the merchants and property owners opposed the idea. They feared that paid parking would discourage people from coming to the area at all. Customers and tenants, they assumed, would simply go to shopping centers like Plaza Pasadena that offered free parking. Meter proponents countered that employees rather than customers occupied many curb spaces, and making these spaces available for short-term parking would attract more customers. Any customers who left because they couldn’t park free would also make room for others who were willing to pay if they could find a space, and who would probably spend more money in Old Pasadena if they could find a space.

Debates about the meters dragged on for two years before the city reached a compromise with the merchants and property owners. To defuse opposition, the city offered to spend all the meter revenue on public investments in Old Pasadena. The merchants and property owners quickly agreed to the proposal because they would directly benefit from it. The city also liked it because it wanted to improve Old Pasadena, and the meter revenue would pay for the project.

The desire for public improvements that would attract customers to Old Pasadena soon outweighed fear that paid parking would drive customers away. Businesses and property owners began to see the parking meters in a new light—as a source of revenue. They agreed to an unusually high rate of $1 an hour for curb parking, and to the unusual policy of operating the meters on Sundays and in the evenings when the area is still busy with visitors. The city also didn’t lose anything in the process. Because there had been no parking meters anywhere in the city before, returning the revenue to Old Pasadena didn’t create a loss to the city’s general fund. Indeed, the city gained revenue from overtime fines. Both business and government thus had a stake in the meter money, and so the project went ahead.

Only the blocks with parking meters receive the added services financed by the meter revenue. The city worked with Old Pasadena’s Business Improvement District (BID) to establish the boundaries of the Old Pasadena Parking Meter Zone (PMZ). The city also established the Old Pasadena PMZ Advisory Board, consisting of business and property owners who recommend parking policies and set spending priorities for the zone’s meter revenues. Connecting the meter revenue directly to added public services and keeping it under local control are largely responsible for the parking program’s success. “The only reason meters went into Old Pasadena in the first place,” said Marilyn Buchanan, chair of the Old Pasadena PMZ, “was because the city agreed all the money would stay in Old Pasadena.”

Only the blocks with parking meters receive the added services financed by the meter revenue. The city worked with Old Pasadena’s Business Improvement District (BID) to establish the boundaries of the Old Pasadena Parking Meter Zone (PMZ). The city also established the Old Pasadena PMZ Advisory Board, consisting of business and property owners who recommend parking policies and set spending priorities for the zone’s meter revenues. Connecting the meter revenue directly to added public services and keeping it under local control are largely responsible for the parking program’s success. “The only reason meters went into Old Pasadena in the first place,” said Marilyn Buchanan, chair of the Old Pasadena PMZ, “was because the city agreed all the money would stay in Old Pasadena.”

The city installed the parking meters in 1993, and then borrowed $5 million to finance the “Old Pasadena Streetscape and Alleyways Project,” with the meter revenue dedicated to repaying the debt. The bond proceeds paid for street furniture, trees, tree grates, and historic lighting fixtures throughout the area. Dilapidated alleys became safe, functional pedestrian spaces with access to shops and restaurants. To reassure businesses and property owners that the meter revenues stayed in Old Pasadena, the city mounted a marketing campaign to tell shoppers what their meter money was funding.

As the area attracted more pedestrian traffic, the sidewalks needed more maintenance. This would have posed a problem when Old Pasadena relied on the city for cleaning and maintenance, but now the BID has meter money to pay for the added services. The BID has arranged for daily sweeping of the streets and sidewalks, trash collection, removal of decals from street fixtures, and steam cleaning of Colorado Boulevard’s sidewalks twice a month. Dedicating the parking meter revenue to Old Pasadena has thus created a “virtuous cycle” of continuing improvements. The meter revenue pays for public improvements, the public improvements attract more visitors who pay for curb parking, and more meter revenue is then available to pay for more public improvements.

Old Pasadena’s 690 parking meters yielded $1.2 million net parking revenue (after all collection costs) to fund additional public services in FY 2001. The revenue thus amounts to $1,712 per meter per year. The first claim on this revenue is the annual debt service of $448,000 that goes to repay the $5 million borrowed to improve the sidewalks and alleys. Of the remaining revenue, $694,000 was spent to increase public services in Old Pasadena, above the level provided in other commercial areas. The city provides some of these services directly; for example, the Police Department provides additional foot patrols, and two horseback officers on weekend evenings, at a cost of $248,000. The parking enforcement officers who monitor the meters until well into the night further increase security, at no additional charge. The city also allocated $426,000 of meter revenue for added sidewalk and street maintenance and for marketing (maps, brochures, and advertisements in local newspapers). Drivers who park in Old Pasadena finance all these public services, at no cost to the businesses, property owners, or taxpayers.

Old Pasadena’s 690 parking meters yielded $1.2 million net parking revenue (after all collection costs) to fund additional public services in FY 2001. The revenue thus amounts to $1,712 per meter per year. The first claim on this revenue is the annual debt service of $448,000 that goes to repay the $5 million borrowed to improve the sidewalks and alleys. Of the remaining revenue, $694,000 was spent to increase public services in Old Pasadena, above the level provided in other commercial areas. The city provides some of these services directly; for example, the Police Department provides additional foot patrols, and two horseback officers on weekend evenings, at a cost of $248,000. The parking enforcement officers who monitor the meters until well into the night further increase security, at no additional charge. The city also allocated $426,000 of meter revenue for added sidewalk and street maintenance and for marketing (maps, brochures, and advertisements in local newspapers). Drivers who park in Old Pasadena finance all these public services, at no cost to the businesses, property owners, or taxpayers.

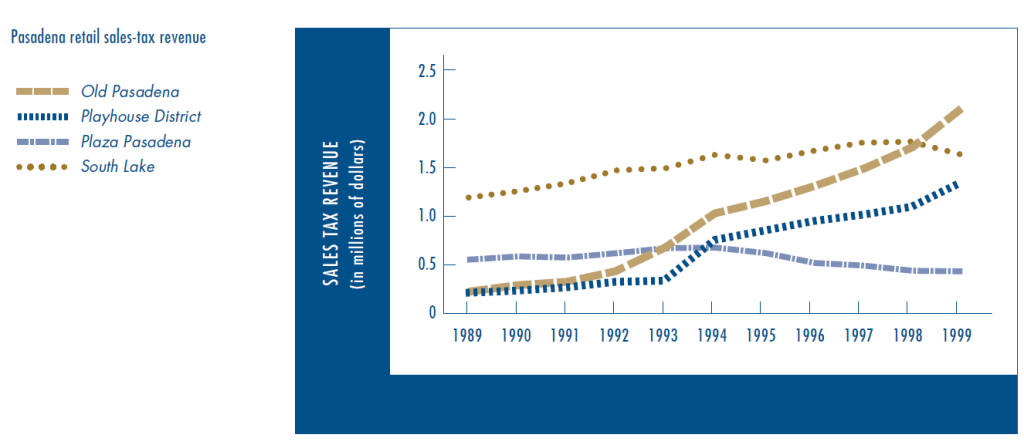

Old Pasadena has done well in comparison with the rest of Pasadena. Its sales tax revenue increased rapidly after parking meters were installed in 1993, and is now higher than in the other retail districts in the city. Old Pasadena’s sales tax revenues quickly exceeded those of Plaza Pasadena, the nearby shopping mall that had free parking. With great fanfare, Plaza Pasadena was demolished in 2001 to make way for a new development—with storefronts that resemble the ones in Old Pasadena.

Would Old Pasadena be better off today with dirty sidewalks, dilapidated alleys, no street trees or historic street lights, and less security, but with free curb parking? Clearly, no. Old Pasadena is now a place where everyone wants to be, rather than merely another place where everyone can park free.

A Tale Of Two Business Districts’ Parking Policies

To see how parking policies affect urban outcomes, we can compare Old Pasadena with Westwood Village, a business district in Los Angeles that was once as popular as Old Pasadena is now. In 1980, anyone who predicted that Old Pasadena would soon become hip and Westwood would fade would have been judged insane. However, since then the Village has declined as Old Pasadena thrived. Why?

To see how parking policies affect urban outcomes, we can compare Old Pasadena with Westwood Village, a business district in Los Angeles that was once as popular as Old Pasadena is now. In 1980, anyone who predicted that Old Pasadena would soon become hip and Westwood would fade would have been judged insane. However, since then the Village has declined as Old Pasadena thrived. Why?

Except for their parking policies, Westwood Village and Old Pasadena are similar. Both are about the same size, both are historic areas, both have design review boards, and both have BIDS. Westwood Village also has a few advantages that Old Pasadena lacks. It is surrounded by extremely high-income neighborhoods (Bel Air, Holmby Hills, and Westwood) and is located between UCLA and the high-rise corridor of Wilshire Boulevard, which are both sources of many potential customers. Old Pasadena, by contrast, is surrounded by moderate-income housing and low-rise office buildings. Tellingly, although Westwood Village has about the same number of parking spaces as Old Pasadena, merchants typically blame a parking shortage for the Village’s decline. In Old Pasadena, parking is no longer a big issue. A study in 2001 found that the average curb-space occupancy rate in Old Pasadena was 83 percent, which is about the ideal rate to assure available space for shoppers. The meter revenue has financed substantial public investment in sidewalk and alley improvements that attract visitors to the stores, restaurants, and movie theaters. Because all the meter revenue stays in Old Pasadena, the merchants and property owners understand that paid parking helps business.

In contrast, Westwood’s curb parking is underpriced and overcrowded. A 1994 parking study found that the curb-space occupancy rate was 96 percent during peak hours, making it necessary for visitors to search for vacant spaces. The city nevertheless reduced meter rates from $1 to 50¢ an hour in 1994, in response to merchants’ and property owners’ argument that cheaper curb parking would stimulate business. Off- street parking in any of the nineteen private lots or garages in Westwood costs at least $2 for the first hour, so drivers have an incentive to hunt for cheaper curb parking. The result is a shortage of curb spaces, and underuse of the off-street ones. The 1994 study found that only 68 percent of the Village’s 3,900 off-street parking spaces were occupied at the peak daytime hour (2 p.m.). Nevertheless, the shortage of curb spaces (which are only 14 percent of the total parking supply) creates the illusion of an overall parking shortage. In contrast to Old Pasadena, Westwood’s sidewalks and alleys are crumbling because there is no source of revenue for repairing them—the meter revenue disappears into the city’s general fund.

In contrast, Westwood’s curb parking is underpriced and overcrowded. A 1994 parking study found that the curb-space occupancy rate was 96 percent during peak hours, making it necessary for visitors to search for vacant spaces. The city nevertheless reduced meter rates from $1 to 50¢ an hour in 1994, in response to merchants’ and property owners’ argument that cheaper curb parking would stimulate business. Off- street parking in any of the nineteen private lots or garages in Westwood costs at least $2 for the first hour, so drivers have an incentive to hunt for cheaper curb parking. The result is a shortage of curb spaces, and underuse of the off-street ones. The 1994 study found that only 68 percent of the Village’s 3,900 off-street parking spaces were occupied at the peak daytime hour (2 p.m.). Nevertheless, the shortage of curb spaces (which are only 14 percent of the total parking supply) creates the illusion of an overall parking shortage. In contrast to Old Pasadena, Westwood’s sidewalks and alleys are crumbling because there is no source of revenue for repairing them—the meter revenue disappears into the city’s general fund.

The Old Pasadena/Westwood Village comparison suggests that parking policies can help some areas rebound, and leave other areas trapped in a slump. If Westwood Village had always charged market prices for curb parking and had spent the revenue on public services, it probably would have retained its original luster rather than fallen into a long economic decline. If Old Pasadena had kept curb parking free and not spent $1.2 million a year on public services, it probably would still be struggling. The exactly opposite parking policies in Westwood Village and Old Pasadena have surely helped determine their different fates. As the signs on Old Pasadena’s parking meters say, “Your meter money makes a difference.”

Conclusion

Charging market prices for curb parking and returning the meter revenue for public improvements have helped pave the way for Old Pasadena’s renaissance. The meter revenue has paid to improve the streetscape and to convert alleys into pleasant walkways with shops and restaurants. The additional public spending makes the area safer, cleaner, and more attractive for both customers and businesses. These public improvements have increased private investment, property values, and sales tax revenues. Old Pasadena has pulled itself up by its parking meters.

Further Readings

Douglas Kolozsvari. Parking: The Way to Revitalization. A Case Study on Innovative Parking Practices in Old Pasadena. Comprehensive project submitted for the Master of Arts in Urban Planning, UCLA, 2002.

Donald Shoup, “Cashing in on Curb Parking,” Access, no. 4, Spring 1994, pp. 20–26.

Donald Shoup, “An Opportunity to Reduce Minimum Parking Requirements,” Journal of the American Planning Association, vol. 61, no. 1, Winter 1995, pp. 14–28.

Donald Shoup, “Buying Time at the Curb,” in The Half-Life of Policy Rationales: How New Technology Affects Old Policy Issues, Fred Foldvary and Daniel Klein, eds. (New York: New York University Press, 2003).

Donald Shoup, “The Ideal Source of Local Public Revenue,” Regional Science and Urban Economics, forthcoming.

Donald Shoup, The High Cost of Free Parking. (Chicago: The Planners Press of the American Planning Association, forthcoming.)