When the Century Freeway opened in October 1993 after three decades in the making – the product of intensive civic conflict, and advertised as the world’s most costly road at over $100 million per mile – it was indeed an achievement of the century. Ultimately it was far more than a mere road. It also became a community development enterprise, an environmental improvement program, a housing project, and a legal precedent that may well shape all future freeway construction. To assess its significance we’ve been examining the record and interviewing the participants, and we will now summarize our findings.

Evolution of the Century Freeway

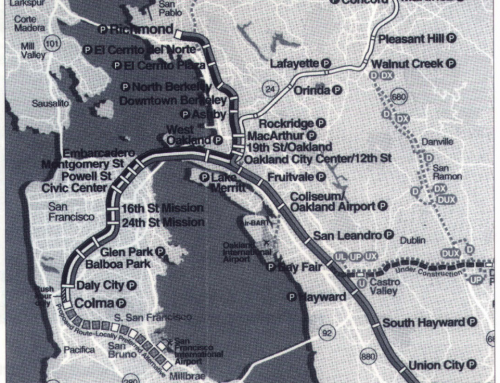

As originally planned, the Century Freeway was to run east to west from San Bernardino to the then-proposed Pacific Coast Freeway west of the Los Angeles International Airport (LAX). It was to be another link to assure that no Angeleno would live more than three miles from a freeway (see map on page 3).

In 1959 engineers deleted the eastern thirty-four miles of the route in favor of a seventeen-mile stretch from LAX to the San Gabriel Freeway. Originally the freeway was to be a ten-lane facility of mixed flow lanes with twenty interchanges serving ten municipalities. The project was to be completed by 1977 after a five-year construction period. But little went as planned. It was dubbed at various stages as the “last urban freeway” and the “world’s most expensive road.”

Early Opposition

Almost from inception, the Century was controversial. It resembled other freeways conceived, planned, or built during that time – a turbulent era of social activism and revolutionary regulatory law, including statutes mandating environmental protection. Highway agencies, such as the venerable California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), were troubled by the Arab oil embargo, high inflation, and the resulting volatile gasoline prices, reduced investments in state highway construction, and departmental personnel cutbacks.

Opposition to the Century came almost immediately. The city of Norwalk fought successfully to eliminate 1.5 miles of roadway east to the Santa Ana Freeway (I-5), which many transportation planners considered a natural junction. At the other end of the proposed freeway, Inglewood succeeded in having the western portion of the freeway moved to its south to bisect the central business district of Hawthorne. Then Hawthorne authorities refused to sign a freeway agreement for this route, forcing realignment to skirt both cities’ borders.

As the concept of environmental impact assessment emerged, officials in 1969 engaged Gruen Associates to identify the adopted freeway alignment’s effects on the surrounding community. But by the early 1970s – despite a successful referendum opposing the road sponsored by the “Freeway Fighters,” an activist group in Hawthorne, and other protests – most cities had executed freeway agreements.

Civil Rights and Environmental Obstacles

On March 3, 1970, Esther Keith, a resident of the corridor, locked her front door and refused to let the right-of-way agent from the Division of Highways enter her home. Her attitude reflected many other residents’ and foreshadowed a significant change in the freeway construction process.

One month before the scheduled groundbreaking in February 1972, the Center for Law in the Public Interest filed a federal lawsuit on behalf of the Keiths, three other couples living within the proposed right-of-way, and several national civil rights and environmental organizations. This suit, Keith v. Volpe, sought an injunction to prevent the state from acquiring property until environmental impact statements were approved. The complaint also alleged inadequate relocation assistance, denial of equal protection to minorities and low-income corridor residents, inadequate public hearings, and violation of due process.

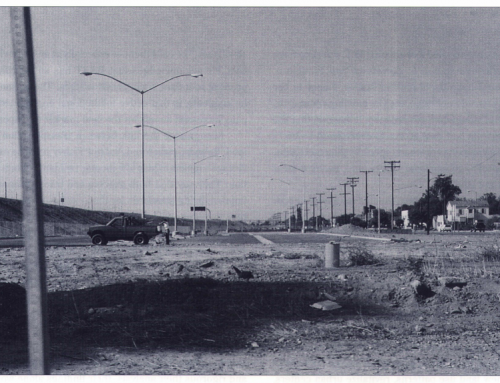

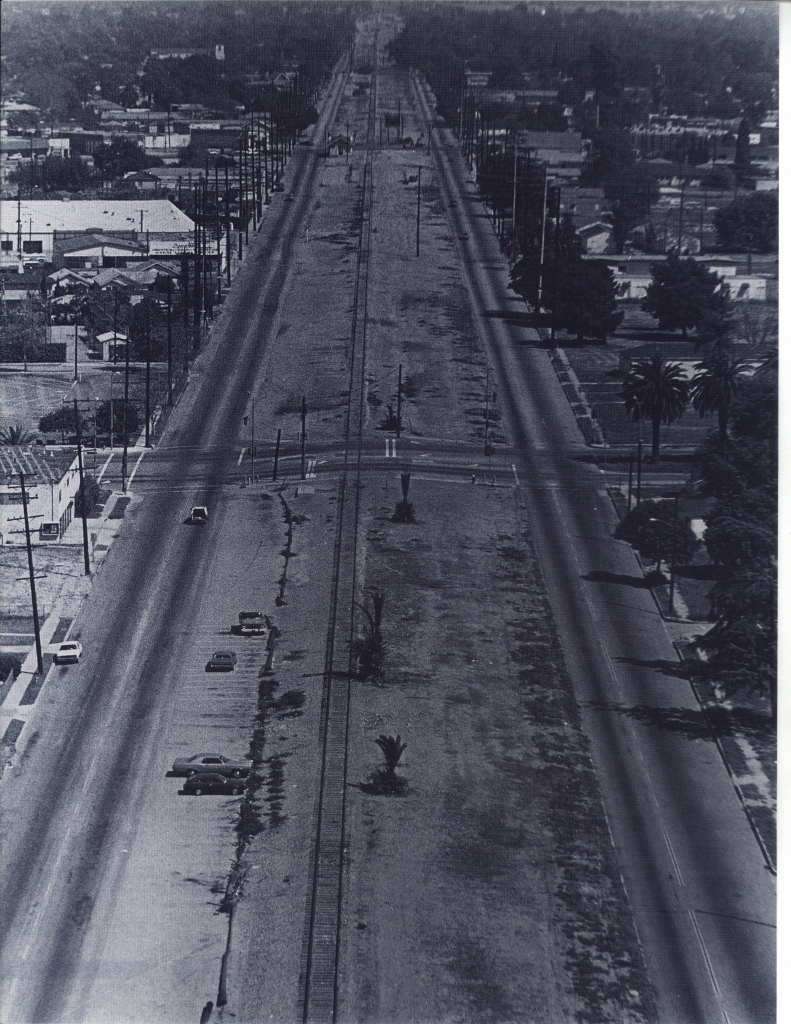

US District Court Judge Harry Pregerson ordered the government to refrain from evicting anyone living along the route of the proposed freeway and from instituting any new acquisition proceedings other than those involving volunteer relocation or those necessary to protect public health and safety. By then 55 percent of the needed parcels had been acquired and 35 percent had been cleared. This ruling halted freeway construction for the next seven years, inducing deterioration in abandoned neighborhoods.

The complaint also alleged inadequate relocation assistance, denial of equal protection to minorities and low-income corridor residents, inadequate public hearings, and violation of due process.

Further uncertainty followed changes in political administration. In December 1975, Governor Jerry Brown suggested that the facility be reduced to four lanes, reinforcing his opposition to major new freeways in Los Angeles. President Carter issued his Urban and Regional Policy, which defined transportation as an incentive program to leverage public and private urban revitalization for economic, environmental, and social goals. Against this backdrop, those who opposed the Century Freeway’s existing plan had an advantage. But the corridor cities themselves insisted that the full ten-lane facility be constructed.

In 1979 the plaintiffs and Caltrans reached an initial agreement recorded in a consent decree. But the Century remained in controversy because the parties had different definitions of a consent decree (a judicially-sanctioned agreement that contains elements of both contract and injunction) and because it was unclear whether the decree derived its force from the original court ruling or from the agreement between the parties themselves. In this case, the decree reflected a strong federal court judge’s persistent efforts to implement the freeway in the best interests of corridor residents.

The consent decree, a very unusual approach to freeway implementation, has been closely followed as a means of incorporating community and environmental considerations in highway building elsewhere. It provided for participation by the Center for Law in the Public Interest, a federal judge, an affirmative action watchdog committee, a designated advocate for displaced residents, the state housing agency, Caltrans, and FHWA.

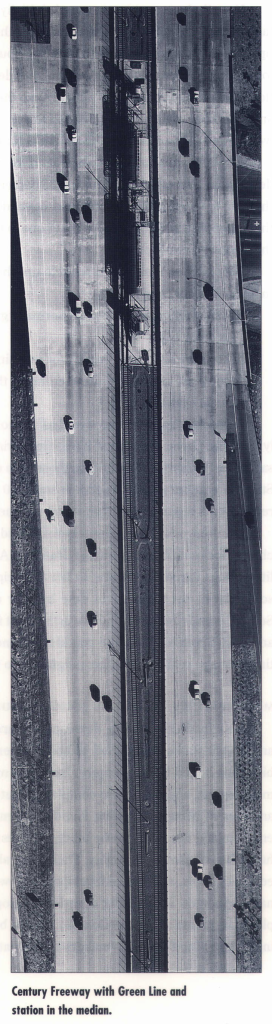

Two and a half years later, the court and parties approved an amended consent decree, stating that the project would have six lanes for general traffic; two HOV lanes; a median busway not wider than 64 feet, convertible to light rail; metered ramps; and new construction of 3700 housing units.

The decree mandated several innovative, unprecedented elements for an interstate highway project. First, it established an Office of the Advocate for Corridor Residents responsible for representing persons displaced by the freeway.

Second, it created an ambitious housing program headed by the State Department of Housing and Community Development, with 4200 units planned. By the time 50 percent of freeway construction contracts were awarded, at least 30 percent of the housing units were to be available for occupancy. For the first time, a project used federal highway funds to assist not only people actually displaced by the freeway, but also to restock the supply in communities that lost housing through right-of-way acquisition.

Third, the decree formed a 60-member Housing Advisory Committee that consulted and assisted the Project Director and held public hearings on the Housing Plan.

Fourth, it began the Century Freeway Affirmative Action Committee, a group comprising community activists and the parties, which monitored and enforced affirmative action requirements. It set employment goals for minorities and women and oversaw contractor compliance and an apprenticeship program for prospective construction workers.

The consent decree saved the Century from the fate of other urban freeways that were terminated during this period: the Westway, the I-40 through Overton Park, the Vieux Carre. Some think it accomplished even more by encouraging enlightened transportation planning, implementing a freeway in response to the needs of all relevant parties. An October 14, 1979, Los Angeles Times editorial opined: ‘The benefits, we think, eventually will extend well beyond the narrow Century corridor to all highway and transportation projects around the country. The real meaning of the Century project is that the good old ways are gone.”

But other observers believe the Century experience should never be repeated – that the consent decree process made it the most expensive urban freeway of the time. (The Boston Artery probably holds that dubious distinction today.) Critics say the suit and consent decree allowed for meddling in transportation affairs by people who, despite good intentions, crippled the project. Indeed, a decade later the Times published an extensive expose on how the sensitive project was actually not very sensitively implemented.

The Century’s Benefits and Costs

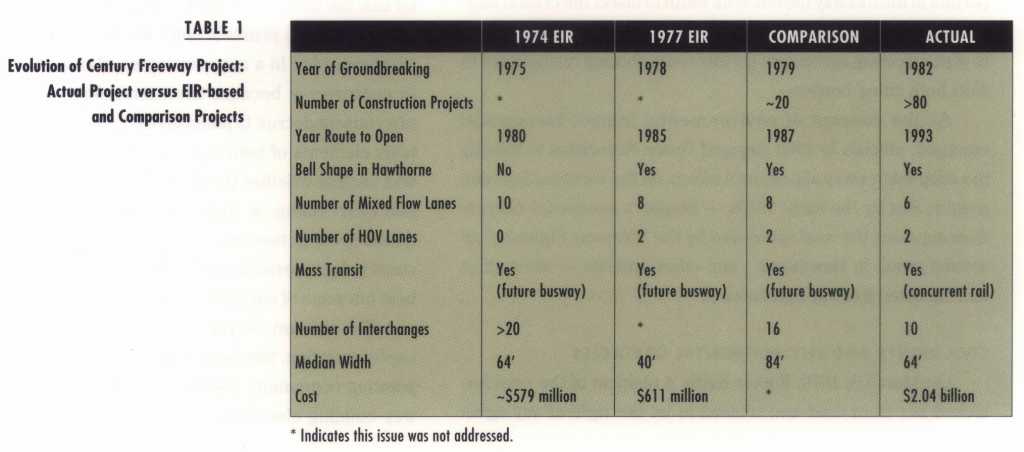

With the important exception of local elected officials, the majority of officials interviewed think that the Century’s benefits outweigh its costs. But were benefits superior to what they may have been without the extraordinary legal resolution? To determine the impact of the consent decree on the project, we created an alternative development scenario (Comparison Project in Table 1) in the absence of the consent decree that accounted for the period’s major changes in environmental law and transportation regulation.

Perceptions of Officials: Costs and Benefits by Category

State transportation officials perceived that both the actual and the alternative project would have net positive environmental impacts. Local officials perceived both projects to have net negative environmental impacts.

The two levels of government also viewed the housing programs differently: Local officials regarded the actual freeway’s housing program as the lesser of two evils. They thought both the actual and alternative projects diminished affordable housing supply and local housing supply and did not adequately mitigate the loss of units taken in the right-of-way acquisition. The goals of the consent decree – to avoid depleting the housing stock in affected communities – did not satisfy them.

Caltrans officials perceived the actual freeway as positively affecting local housing supply and local affordable-housing supply, and viewed the alternative project as having negative effects.

Both local officials and Caltrans officials were generally dissatisfied with the consent decree’s transportation effects. They judged congestion on parallel arterials, other area freeways, and other surface streets, and the overall movement of goods and people through the corridor as worse under the actual project.

parallel arterials, other area freeways, and other surface streets, and the overall movement of goods and people through the corridor as worse under the actual project.

Still, most of the Caltrans staff we interviewed, while disapproving any reduction in lanes and local interchanges, perceived the construction of the freeway mandated by the consent decree to be good public policy. The decree allowed the road to be constructed. Caltrans officials predicted inadequate service associated with downscaling the freeway but concluded that “six lanes are better than nothing.”

Local officials believed that the relatively small number of local interchanges limited opportunities for economic growth at subcenters near interchanges. Although the decree required access to LAX, there remains no direct link to the airport. Travelers use other roads or take a bus.

In contrast, all groups surveyed unanimously acknowledged the positive effects of the consent decree for all intended beneficiaries of the affirmative action provisions.

Many Caltrans officials, who initially viewed the consent decree as a threat to the department’s autonomy, appear to have eventually acknowledged the decree’s value. Local officials, on the other hand, perhaps because they were neither official parties to the lawsuit nor active participants in crafting the decree, rejected the notion that the consent decree was a necessary key to building a “sensitive freeway.”

Corridor Residents: Users and Non Users

Ultimately the true measure of a transportation system’s success is reflected in its actual use. It’s no surprise that the Century is widely used: ADT is 162,000 to 200,000 on the eastern portion; 215,000 in the center; and 110,000 to 168,000 in the west. The Green Line, a light-rail system that runs for twenty miles along the freeway median, averages 15,000 trips on week days and half that number on weekends.

Nonetheless, many more people initially intended to use the facility than do so today. Before and after the Century Freeway opened, we surveyed corridor residents about their travel behavior. Seventy-six percent of those who intended to use the mixed flow lanes for nonwork trips actually use the lanes. Of the very small number of those who intended to use the carpool lanes for work trips, only a quarter of them are actually doing so.

A notable number of respondents have changed their route, destination, or mode choice. Almost 35 percent said they changed their route to work after the freeway opened; 8 percent changed their shopping location; and just over one in ten now carpools on the Century Freeway.

Why have so many chosen not to use the facility? The three most commonly cited reasons:

(1) It does not go where people normally go for work and for other trips.

(2) There are alternative means for reaching a destination.

(3) People are concerned about crime on the Green Line transit system.

Regarding transit crime, over half of those who have actually used the Green Line found it free from crime and assessed its safety much more positively than those who did not use the line. Still, the number of actual users is small: 80 percent of corridor respondents reported that they never use the Green Line.

For nonwork trips, mean travel time did not change but the change for work trips was rather dramatic. Although we can say little about carpoolers since so few participated in our study, solo drivers cut their travel time by four minutes. However, South Central residents who live in the least favorable economic and social conditions in the corridor, did not share the traveltime savings realized by their neighbors to the east and west.

Municipalities: Land Use Policy Influence

Anticipating booming development around interchanges and transit stations predicted by some experts, a few cities had big plans linked to the Century, including mammoth entertainment, sports, and mixed-use complexes. But our interviews and analyses of plans and zoning found the Century’s overall influence on land use policy to be modest. Cities recognize possible future benefits from the facility: Their general plans discuss related policy tools, such as redevelopment powers or zoning ordinance changes, in fostering corridor development. But general plan statements about the Century remain broad and overarching, suggesting that policymakers prefer watchful waiting.

Zoning changes were mixed. Within one mile of the Century, four cities deintensified their zoning, two cities intensified zoning, and one city made no change. Of all the zoning changes that did occur in that vicinity, about a third involved new residential designations.

Conclusion

The Century Freeway emerged from conflict-ridden beginnings to become one of the first freeways governed by a consent decree. Today the policymakers who conceived it, the engineers who designed it, the people displaced by it, and the drivers who use it, have reached different verdicts on its benefits and costs.

Certain differences will no doubt recede into history. Opponents of the Century will recognize its usefulness; proponents will see its failure to deliver all benefits promised. People will try the Green Line and adapt to rail travel. Interfreeway HOVs will become less intimidating – and more attractive as ADT builds. Modest additional transit-oriented development may sprout up. Debates over housing types and affirmativeaction beneficiaries will be forgotten. The lavish landscape mitigation requirements will become commonplace.

But when the decision-making process involves a wide range of parties, like those involved with the Century, full consensus will remain elusive. Any urban freeway will only emphasize divergent versions of ideal community development in the United States.

Further Readings

Joseph DiMento, Jace Baker, Robert Detlefsen, Drusilla van Hengel, Dean Hestermann. and Brenda Nordenstam, ”Court Intervention, the Consent Decree, and The Century Freeway,” Research Technical Agreement, Caltrans, No. F89CN62, RTA-54J273, 1991.

Joseph DiMento, Brenda Nordenstam, Dean Hestermann, and Drusilla van Hengel, “Regional Projects/Local Concerns: Urban Freeways, Citizen Participation and Community,” Final Report, Haynes Foundation, University of California, Irvine, 1 992.

Dean Hestermann, Joseph F . DiMento, Drusilla van Hengel, and Brenda Nordenstam, ‘*Impacts of a Consent Decree on ‘The Last Urban Freeway’: Interstate 105 In Los Angeles County,” Transportation Research A, Vol. 27A, No. 4, 1993, pp. 299-313.

Drusilla van Hengel, ” Citizens Near the Path of Least Resistance: Travel Behavior of Century Freeway Corridor Residents,” Ph.D. Dissertation, University of California, Irvine, 1996.