ACCESS 09, Fall 1996

Introduction

Luci Yamamoto

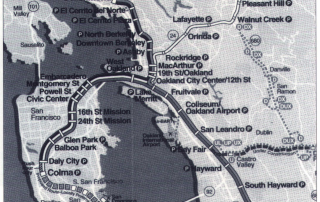

Several years ago, I commuted to work on BART, traveling from Oakland's Rockridge station to downtown San Francisco. Although I could have used another station closer to my Berkeley home, I preferred Rockridge, with its bustling commerce, well-lit sidewalks, and village-like atmosphere. It seemed that the neighborhood's residents had easy access to everything: a variety of restaurants, a library, supermarkets and specialty gourmet shops, health clubs, bookstores, professional offices, and, perhaps most significantly, buses and BART.