Mel Webber taught both planning theory and transportation policy to graduate students in the Department of City and Regional Planning. I had the good fortune to co-teach the transportation policy class with him in the late 1980s, shortly before his retirement from the department. We each took responsibility for some of the sessions, but both of us participated in nearly every class.

When it was Mel’s turn, he rarely lectured. Sometimes he started the class with a slide show or a few transparencies, then opened up the session to discussion. At other times he came to class with brief introductory remarks and an example or two, plus a list of questions to debate.

He brought his personal experiences, good and bad, into the classroom to make his lessons concrete. Mel showed students how BART, which he had initially advocated, provided too sparse a network of services to transform urban space as he had once thought it would. Students challenged him: Surely the lack of supportive land use policies had reduced BART’s effectiveness. Mel thought that over and came back with readings on how transportation benefits should be capitalized into real estate values, as well as case studies of the zoning fights that had limited urban intensification around key BART stations. It was a successful exchange, in his view: conflicting viewpoints were uncovered and explored and everyone’s perspective broadened.

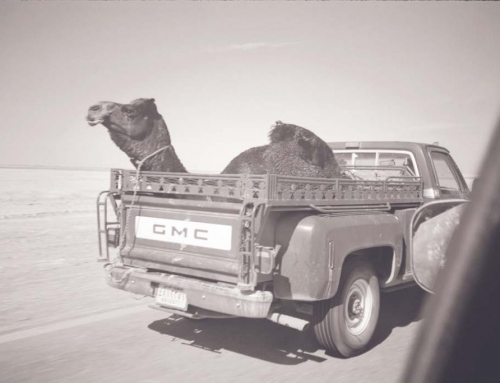

Mel loved his car and believed that personal vehicles were the ideal mode of transport, offering door to door service at the driver’s own schedule. The only problem with cars, he thought, was that some people couldn’t drive them. He was dubious about environmentalists’ criticisms of auto dominance, convinced that technology and better planning could reduce harm to minimal levels. Still, he could be convinced by data. Seeking to teach students how evaluations based on “average” emissions can produce bad policy, I used Mel’s old Volvo to illustrate how cars lacking modern emissions technology produce pollution far disproportionate to the miles they are driven. Mel did some research of his own on emissions and fuel economy, and (with some regrets) replaced the car with a new model the next time the Volvo needed a major repair.

Mel loved his car and believed that personal vehicles were the ideal mode of transport, offering door to door service at the driver’s own schedule. The only problem with cars, he thought, was that some people couldn’t drive them. He was dubious about environmentalists’ criticisms of auto dominance, convinced that technology and better planning could reduce harm to minimal levels. Still, he could be convinced by data. Seeking to teach students how evaluations based on “average” emissions can produce bad policy, I used Mel’s old Volvo to illustrate how cars lacking modern emissions technology produce pollution far disproportionate to the miles they are driven. Mel did some research of his own on emissions and fuel economy, and (with some regrets) replaced the car with a new model the next time the Volvo needed a major repair.

One thing that Mel insisted on was that alternative viewpoints be sought out and given a hearing. He was skeptical of “true believers” of any type, but especially those who seemingly knew how others should live. Planning’s great contributions, in Mel’s view, were its ability to help people identify and evaluate options, and its aim of leveling the playing field. With good information and a fair set of choices, people then could decide what was best for themselves.

Students often were a bit in awe of Mel at the start of the semester. He was, after all, one of the founders of the department, the director of the Institute of Urban and Regional Development, the author of seminal works. The students quickly learned that he thought of them as fellow professionals. He wanted to hear about their experiences in the world of work and to find out what issues they saw as pressing. He listened to what they had to say with attentiveness and interest. His office door was open to their visits and his mind was open to their ideas. He might disagree, but his disagreement was gently offered, in the form of questions to think about and articles to read. Many of the students became regular visitors. A significant number continued their visits long after the class had ended.

Mel insisted that alternative viewpoints be sought out and given a hearing.

When Mel retired from City and Regional Planning, he missed the regular contact with students. He was pleased whenever a PhD student would seek him out, finding the way to his office at the UC Transportation Center (UCTC) on the opposite side of campus from his old Wurster Hall digs. (Ironically, he had come full circle: the old Naval Architecture Building that housed UCTC for many years had been the home of City and Regional Planning when Mel was a student and a young faculty member there.)

As UCTC’s first director, Mel found new ways to work with students. He created a UCTC dissertation grant program that offered ten fellowships a year, available to support transportation dissertations at any UC campus. He recruited recent transportation PhDs to review the grant proposals and choose the winners. He read the dissertations that began to arrive and recruited some of their authors to write articles for ACCESS. He established an annual student-led conference and participated in it every year until his failing health limited travel. Mel never quit teaching; he just changed the form of teaching he did.