Target Comes to Davis

Davis, California, is well-known in transportation circles for having the highest share of bicycle commuters in the US, due in large part to pioneering efforts starting in the 1960s that created an extensive bicycling network. Less well-known is the substantial effort Davis has made to avert the kind of sprawl found in most US cities. Multi-family housing is distributed throughout the city, neighborhood shopping centers are within a short bike ride for most residents, and the city has improved sidewalks, landscaping, and public spaces to promote its traditional downtown. Davis restricts development beyond the current urban boundary while at the same time encouraging infill development within the boundary. As a result, Davis is the sixth densest urbanized area in the US and an exemplar of what small cities can achieve with coordinated policies and careful planning.

Consequently, when the Target Corporation proposed opening a store in Davis in the mid-2000s, a fiery debate erupted. At the time, the city’s General Plan deemed “warehouse style retailers … inappropriate given the nature and scale of the Davis market” and restricted retail businesses outside downtown to sizes appropriate for serving small neighborhoods rather than larger regions. The land use code limited store sizes to 30,000 square feet, far less than the proposed 137,000 for the Target store. Though the City Council approved the project in June 2006, it recognized the decision’s combustibility and held a public referendum on the development agreement.

Consequently, when the Target Corporation proposed opening a store in Davis in the mid-2000s, a fiery debate erupted. At the time, the city’s General Plan deemed “warehouse style retailers … inappropriate given the nature and scale of the Davis market” and restricted retail businesses outside downtown to sizes appropriate for serving small neighborhoods rather than larger regions. The land use code limited store sizes to 30,000 square feet, far less than the proposed 137,000 for the Target store. Though the City Council approved the project in June 2006, it recognized the decision’s combustibility and held a public referendum on the development agreement.

Impassioned Davis residents voiced concerns regarding Target’s arrival, including its environmental, economic, fiscal, social, and cultural impacts. Some residents feared that Target would harm local businesses and draw shoppers away from neighborhood centers. Others argued that allowing Target to move into Davis would be a public endorsement of big-box retail, a type of built form thought to be incompatible with the city’s larger sustainability goals and town culture. By contrast, supporters of the project argued that Davis residents already shopped at stores like Target in other cities, and that a Davis Target would fill a retail need, keep sales tax revenues within the city, and reduce driving. In November 2006, 51.5 percent of voters cast their ballots in support of the project, and a Target store finally opened in Davis in October 2009.

Measuring the Changes

Davis is not the first community to debate the desirability of big-box retail. Around the US, communities have adopted policies to restrict stores like Target and Walmart, which are believed to threaten local businesses, offer low-wage jobs with limited benefits, and harm the environment. The opening of the Target store in Davis—the first big-box retailer in the city—gave us a perfect opportunity to test these assumptions. We focused on the two questions most debated in Davis. First, how did Target change residents’ total vehicle travel and greenhouse gas emissions? And second, how did Target affect downtown businesses?

To measure how Target affected Davis, we surveyed residents about their shopping behavior: once just before the opening of the store, and once a year after its opening. In total, 1,018 residents completed the online survey in 2009, and another 1,025 residents did so for the survey in 2010. In analyzing the data, we excluded respondents under age 25 in order to leave out most UC Davis students, whose shopping habits likely differ from those of the general population.

To measure how Target affected Davis, we surveyed residents about their shopping behavior: once just before the opening of the store, and once a year after its opening. In total, 1,018 residents completed the online survey in 2009, and another 1,025 residents did so for the survey in 2010. In analyzing the data, we excluded respondents under age 25 in order to leave out most UC Davis students, whose shopping habits likely differ from those of the general population.

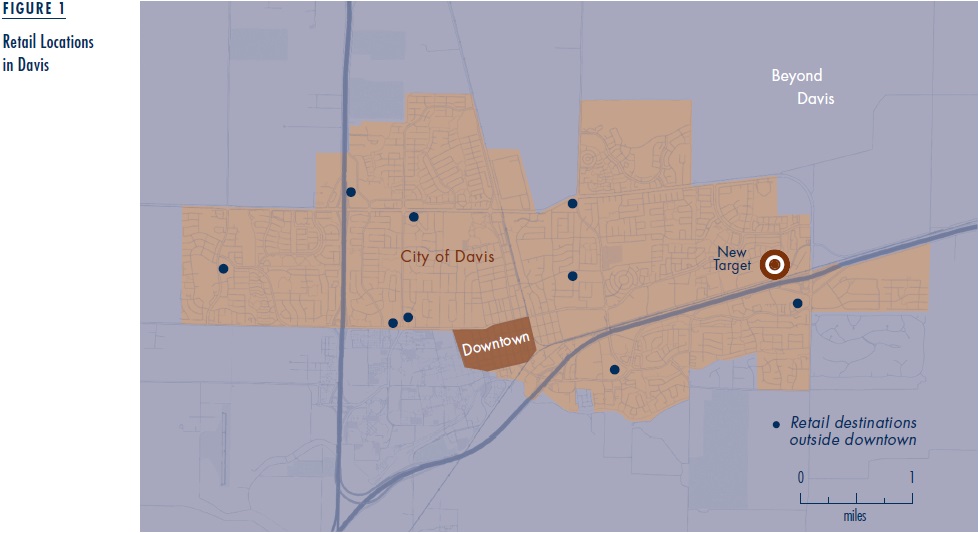

The survey included questions about the frequency and travel mode for trips to different shopping destinations: stores in downtown Davis, other stores in Davis, stores outside of Davis, and, in the second survey, the Target store in Davis. The survey also included questions about online shopping. We asked respondents to focus on shopping for 17 categories of items found at Target other than groceries. For the most recent trip to each destination, respondents reported what kinds of items they purchased and how much they spent. In addition, we asked respondents to give us an intersection near their home so that we could calculate distances to each of the different shopping destinations. We then pieced this information together to estimate the effects of Target’s opening.

Vehicle Miles Traveled

How did the Target store’s opening affect vehicle travel and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions? We estimated the change in VMT for the population as a whole by looking at how often residents shop at different destinations, what modes they used to get there, and whether they stopped there on their way to or from other places.

We estimate that, after Target opened, average monthly shopping VMT declined from 98.4 to 79.5 per person, a drop of nearly 19 miles per month per adult age 25 or over. This decline translates into a savings of over 7.5 million VMT per year, reducing CO2 emissions by 2,0 metric tons, equivalent to the total CO2 emissions from 589 passenger cars for a year.

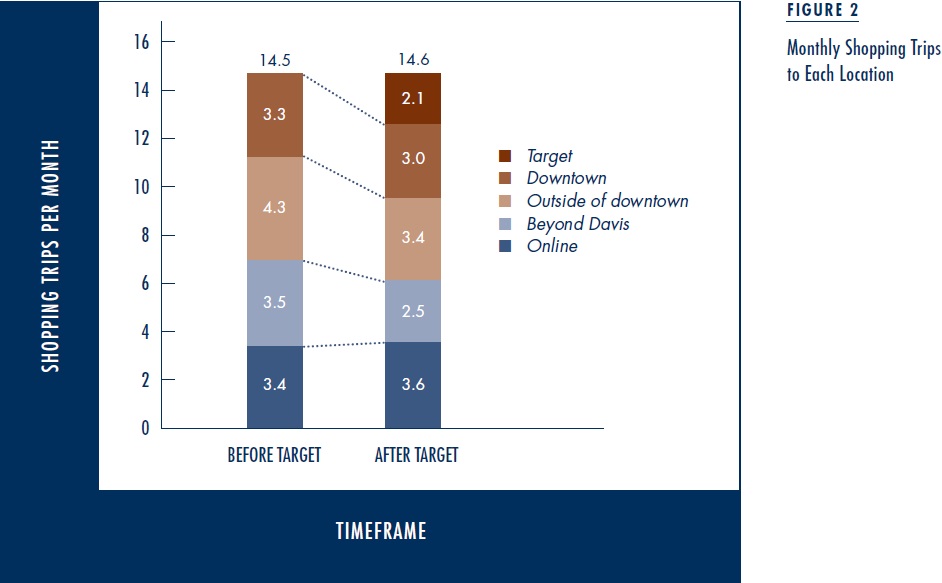

We found that shopping trips shifted in significant ways after the Target opened. Over 90 percent of respondents shopped at least once at Target during its first year, and the average shopper visited 2.1 times per month. As one would expect, trips to other destinations dropped (Figure 2): a small drop in trips to downtown (from 3.3 to 3.0 trips per month), a larger drop to stores outside downtown (from 4.3 to 3.4 trips per month), and the largest drop to stores outside Davis (from 3.5 to 2.5 trips per month). Although total shopping trips declined from 10.3 to 9.5 trips per month, total shopping occasions, including online shopping, stayed relatively stable at around 14 occasions per month.

The geography of local retail was a big factor in changes in vehicle travel and greenhouse gas emissions. On average, respondents live 2.2 miles from downtown, 2.0 miles from other stores in Davis (which are dispersed throughout town), and 3.5 miles from Target (located at the eastern edge of town). Davis is separated from neighboring cities by a wide band of agricultural land, which means that the stores where residents shop outside Davis are on average 18 miles away. Thus, every trip to Target that replaced a trip to a store outside of Davis produced an average of about 15 fewer vehicle miles traveled. The savings were even greater if the trip to Target was “on the way somewhere else,” which was rarely the case for trips to stores outside Davis.

Nearly all trips to stores outside Davis were by car, but within Davis, close to 20 percent of respondents walked, bicycled, or used transit. So when residents shifted from stores outside of Davis to Target in Davis, they were more likely to get there by means other than driving, which also reduced VMT.

Effects On Downtown

How did Target affect downtown businesses? Did the reductions in VMT and GHG emissions come at the expense of downtown? Residents shopped downtown somewhat less often after Target opened. On the other hand, residents made many fewer trips to stores outside downtown Davis, where businesses are more likely to be national chains. Thus, while Target’s arrival coincided with a drop in total trips, chain stores were affected more than locally owned stores.

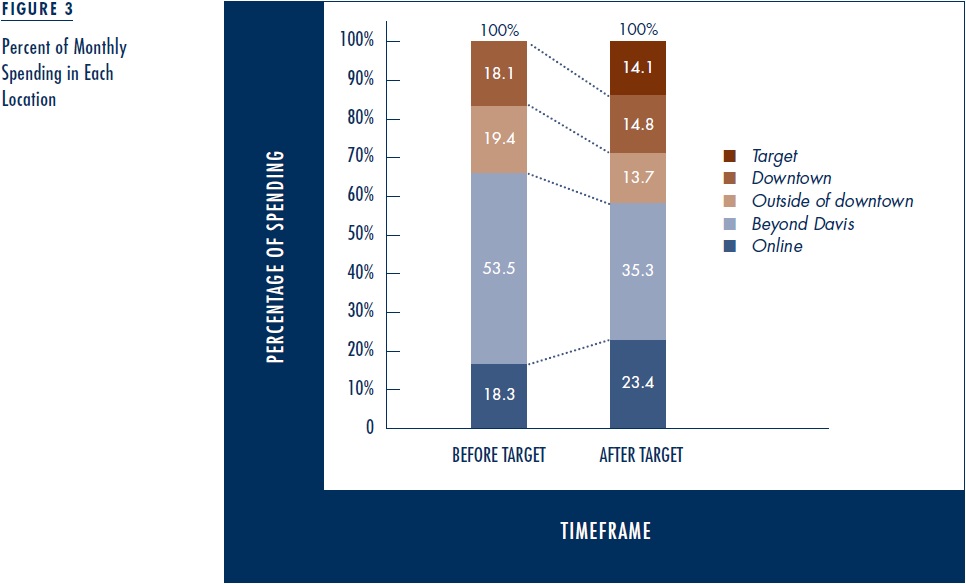

Changes in expenditures on Target-type items mirror the changes in trip frequency. Before Target opened, we estimate that residents had close to $950 per month in total consumer expenditures. They spent about half of this amount at stores outside Davis and just under 20 percent both at downtown stores and at stores in other areas of Davis (Figure 3). After Target opened, overall spending stayed about the same, but spending at Target averaged $128 per month, or about 14 percent of spending. The share of spending outside Davis dropped from one half to just over one-third of overall spending, while the share at Davis stores outside downtown dropped from about 20 to 14 percent. The share of spending in downtown also dropped but less than the share of spending in these other destinations, from 20 percent to 15 percent.

Other results from the survey suggest that downtown shopping is simply different from shopping at Target or elsewhere. Residents shopping downtown are more likely to browse rather than buy and are more likely to shop at locally owned businesses. A series of survey questions on perceptions show that Davis residents see downtown stores as offering higher priced but higher quality products, with a more limited product selection. These stores, residents say, offer more interaction with customers compared with stores elsewhere, but returning items is more difficult and the hours of operation are more limited. Downtown is easier to reach by walking or biking than Target is, but residents find it harder to drive or park there. The only characteristics on which downtown did not differ from Target were the quality and availability of bike parking, rated by residents as high in both locations (this is Davis). Not surprisingly, given the mix of stores downtown, most shopping trips for Target-type items were not to downtown even before Target opened. In other words, Target is not a good substitute for downtown shopping.

Lessons for Other Cities

Davis isn’t like most other American cities. Before Target opened in the city, the nearest Target or Walmart was at least eight miles from the center of Davis, a result of aggressive growth management policies that have preserved the agricultural lands separating Davis from neighboring cities. When Target opened, the average driving time to the nearest big-box store fell by two-thirds. In other cities, the nearest big-box store is probably much closer, and the opening of a new store may not reduce the distance very much. Nonetheless, any reduction in distance to the nearest store could reduce miles driven as long as residents don’t shop more often as a result.

Davis isn’t like most other American cities. Before Target opened in the city, the nearest Target or Walmart was at least eight miles from the center of Davis, a result of aggressive growth management policies that have preserved the agricultural lands separating Davis from neighboring cities. When Target opened, the average driving time to the nearest big-box store fell by two-thirds. In other cities, the nearest big-box store is probably much closer, and the opening of a new store may not reduce the distance very much. Nonetheless, any reduction in distance to the nearest store could reduce miles driven as long as residents don’t shop more often as a result.

Before Target opened, stores in downtown Davis did well in the absence of big-box stores. As a result of their initial vitality, stores in downtown Davis may have been more immune to the Target shock than downtown stores of other communities. On the other hand, many downtowns have already been decimated by the proliferation of chain stores and strip malls to the point where one more big-box store would have little impact. For both healthy downtowns that offer something different from big-box stores, and for struggling downtowns already affected by them, fears about another big-box store may be exaggerated.

Target did not mean the end of life as we know it in Davis. The store added to the shopping options available to residents, and it lowered overall greenhouse gas emissions without seriously harming downtown. The new Target is popular with Davis residents: while just over 50 percent of voters supported the Target store, nearly 90 percent of respondents reported having shopped there a year after its opening. And the share of respondents who agreed with the statement, “It was a good decision to allow a Target store in Davis,” increased from 60 percent before its opening to 68 percent afterwards. Other communities, with the right combination of policies in place, might also find that big-box retail is not so bad.

This article is adapted from “Measuring the Impacts of Local Land-Use Policies on Vehicle Miles of Travel: The Case of the First Big-Box Store in Davis, California,” originally published in the Journal of Transport and Land Use.