Transit operators faced with sharp revenue shortfalls due to the economic downturn have reduced or eliminated feeder bus services. Feeder services often carry only five to ten passengers per run, with costs in the range of $6 to $10 per one-way trip, and so are prime targets for cost-cutting measures. Trunk line routes, in contrast, carry two to three times more riders.

What happens when feeder services disappear or are sharply cut back? Some former users are able to walk to the trunk line bus or rail service, and some can drive to a station, park, and ride transit the rest of the way. But many others, no longer able to navigate their first and last mile on a shuttle, give up and drive to work instead, adding to the traffic load on city streets and freeways.

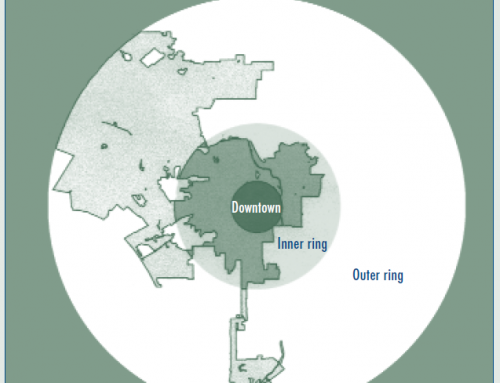

In some communities, innovative shuttle services are filling the gap. Recent studies have identified over 150 such services currently operating in the Bay Area alone. These Bay Area shuttles carry more than eight million riders a year. Employer-operated services connect park-and-ride lots and rail stations to the workplace; cities run shuttles for commuters, school children, hotel visitors, and shoppers; transit agencies operate special services in partnership with major employers. While a few of the employer-operated shuttles are only for that company’s workers, most shuttles are open to the public and free of charge.

Some communities pay for their shuttles through public- private partnerships, with the city contributing some funds and private sector members paying fees. The community shuttles all started as demonstration projects supported by grants; once the service proved successful, permanent public and private financing was secured. Business improvement districts have been a common mechanism for levying the assessment on local businesses. In contrast, single-employer shuttles are mostly self-financed, and many of them originally started as traffic mitigation required as a condition of development approval. Over the years, employees have come to view the shuttles as a valuable benefit. Employers, in turn, see them as a way to enlarge the labor pool accessible to the worksite while keeping traffic manageable and community relations positive.

Recent studies have identified over 150 such services currently operating in the Bay Area alone. These Bay Area shuttles carry more than eight million riders a year.

Shuttle providers in the Bay Area report hourly costs of $50 to $60, about half that of the larger transit operators in the Bay Area and roughly the same as the lowest-cost public providers. Operating and administrative costs typically run $2 to $5 a ride. Providers hold down costs by keeping administrative expenditures low, making cost-effective equipment purchases or leases, and contracting for maintenance, in some cases with the local bus operator’s union employees. In a few cases the transit operator also provides drivers, but most shuttle services hire their own. Wages for drivers are somewhat lower than the union average, but in most cases are at or above union starting salaries.

In some instances, shuttles have allowed employers to reduce the amount of parking they’d otherwise need. The daily cost of providing a parking space in a surface lot ranges from $8 to $15 in most parts of the Bay Area, so employers can save money if they provide shuttle services rather than free parking. Indeed, many employers would find it less expensive to give their workers a free monthly transit pass and free shuttle rides than a free parking space. Unfortunately, most local parking codes fail to take into account this cost-saving, traffic-reducing strategy.

Shuttles are an innovation that clearly deserve more consideration, not only as a way to solve the first and last mile access problem but also to save money and reduce traffic. Possibilities for reforms of local parking requirements and further investigation of markets for shuttles would be high-payoff topics for investigation.

Elizabeth A. Deakin