[sharelines]The local environment affects bus stop safety.

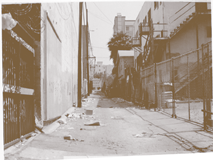

It’s early morning at the bus stop on Central and 7th in downtown Los Angeles. A middle-aged Latino woman is waiting for the bus, nervously clutching a big plastic bag close to her body. There are no pedestrians on the street, just a few parked cars behind a barbed-wire fence. The nearby corner is occupied by a cheap, run-down motel called the Square Deal with a liquor store on the ground floor. A man in ragged clothes appears to be sleeping (or is he dead?), curled up on the sidewalk outside the store, not far from the woman. Broken glass, empty cans, and other trash litter the bus stop where the woman is standing. She nervously surveys the street for the bus. From time to time she throws a fleeting look at the sleeping man. At last the bus arrives, and the woman disappears behind its protective doors.

Fear is a fact of life for hundreds of thousands of inner-city residents who are captive bus riders. They describe bus stops as common settings for crime, providing cover for criminals who hang out waiting for potential victims without arousing suspicion. Inner-city riders are constantly wondering how safe it is to wait for the bus. They say they’re always leery of individuals who stand behind them at bus stops. They’re afraid of strangers, some of them gulping from bottles hidden in shabby brown bags. They’re intimidated by homeless people who hang out at bus stops mumbling obscenities. They’re often overcome by eerie feelings while waiting alone for the bus, surrounded by vacant buildings or fenced lots, with no other human being in sight.

Most of us don’t know such fears because we commute in private cars. The metal cocoons of our automobiles protect us from exposure to the dangers of the public realm. Maybe this is why the plight of bus riders at the inner-city bus stops has not  attracted much attention from the media, nor generated response from transit authorities. Or maybe it’s because many of the victims are poor, immigrants, or nonvoters. Some are even afraid to report a crime to the authorities lest they expose their illegal-resident status.

attracted much attention from the media, nor generated response from transit authorities. Or maybe it’s because many of the victims are poor, immigrants, or nonvoters. Some are even afraid to report a crime to the authorities lest they expose their illegal-resident status.

Typically, transit authorities do not perceive the bus-stop environment as their responsibility and instead concentrate their security measures on the buses and trains. After all, bus stops are on the city’s streets, and they’re no more unsafe than other parts of the urban environment. Approximately 1.2 million people ride Los Angeles buses every year, and only 3,111 bus-stop crime incidents were reported to the transit police in the two-year period 1994–1995. Incidence of serious crime (rape, robber y, and assault) was even lower. Fewer than five violent crimes were reported per 100,000 passengers. However, this offers little comfort to inner-city bus passengers who are victimized at bus stops.

We find a significant spatial concentration of crime incidence at specific places. About half of all reported crimes in Los Angeles are committed within a thirteen-square-mile area that includes downtown and adjacent neighborhoods to the west. There, downtown and inner-city bus lines pass through some of the most neglected, poor, and crime-ridden neighborhoods of the city. So it’s no surprise that these bus stops suffer most from crime. It’s astonishing, however, that within the same overall area, even along the same bus line, bus stops near each other have very different crime rates. Some bus stops seem to be immune to crime, while others are described as “hot spots” of criminal activity. If we take ridership data into account and normalize crime incidence per capita, we still find that some bus stops are much more dangerous than others even though they’re close together and along the same bus routes. Based on criminological research and our own observations, it seems that environmental attributes in the vicinity of a bus stop can play a major role in the safety of the setting and its susceptibility to crime.

Environment and Crime

During the last few decades there’s been a resurgence of interest in the locations of violent behavior and in the importance of space and place as settings for crime. The roots of this emphasis on place are not new. They can be traced to the ecologic studies of the Chicago School in the 1920s and 1930s, when Louis Wirth suspected that physical characteristics of cities significantly affect crime. Chicago sociologists Clifford Shaw and Henry McKay were the first to identify and study crime variations within the same city. But these findings were later disputed and forgotten.

The importance of environmental attributes for crime prevention was revisited in the 1960s and 1970s. Jane Jacobs argued that crime and the physical environment are related in a systematic, observable, and controllable manner. Jacobs viewed natural surveillance—“eyes on the street,” as she put it—as an effective deterrent to criminal activity. Oscar Newman’s studies of crime in public housing elaborated the idea of defensible space—an environmental layout whose physical characteristics can deter criminal activities. He argued that such environments are characterized by location within “safe zones,” surveillance opportunities by residents, and a sense of ownership on the part of neighbors, who are likely to protect “their” space against criminals.

The importance of environmental attributes for crime prevention was revisited in the 1960s and 1970s. Jane Jacobs argued that crime and the physical environment are related in a systematic, observable, and controllable manner. Jacobs viewed natural surveillance—“eyes on the street,” as she put it—as an effective deterrent to criminal activity. Oscar Newman’s studies of crime in public housing elaborated the idea of defensible space—an environmental layout whose physical characteristics can deter criminal activities. He argued that such environments are characterized by location within “safe zones,” surveillance opportunities by residents, and a sense of ownership on the part of neighbors, who are likely to protect “their” space against criminals.

The ideas of Jacobs and Newman prompted a series of public programs on crime prevention through environmental design in the 1970s. But interest in environmental crime prevention languished again in the 1980s, when critics condemned such efforts as pure environmental determinism. In recent years, however, new criminological theories once again emphasized the importance of place and the relationship between built environment and crime. Criminologists spoke persuasively about the “broken windows effect”—signs of disrepair, dereliction, and dilapidation as catalysts for crime. Unrepaired broken windows, uncollected trash, and unkempt streets send messages to potential criminals that no one is in control and that their actions will go unnoticed.

Criminologists also introduced the idea of an environmental backcloth that can influence criminal behavior. This refers to the physical infrastructure and the buildings, roads, transit systems, land uses, and people located within this infrastructure—constellations of certain environmental attributes that seem to be associated with criminal behavior. Criminologists call these high-crime spots “crime generators” or “hot spots.”

Hot Spots at Bus Stops

High-crime bus stops are hot spots. But why do these particular bus stops attract so much crime while other bus stops nearby are much safer? What makes some bus stops so dangerous?

To address these basic questions, we examined the physical and social environments of the ten most dangerous bus stops in the city of Los Angeles. These bus stops were identified from crime data obtained by the transit police for the period of January 1994 through December 1995. Consistent with hot-spot theory, each of these ten bus stops had much more crime than any of the thousands of other bus stops in L.A. More specifically, crime incidents at these ten bus stops during the study period accounted for eighteen percent of the total reported crime incidents at all bus stops. Even after normalizing for crime incidents per capita, a ride r was twenty to thirty times more likely to be victimized at these bus stops than at others in Los Angeles.

r was twenty to thirty times more likely to be victimized at these bus stops than at others in Los Angeles.

A survey of 212 bus riders whom we found waiting at these high-crime bus stops revealed an even higher incidence of crime than was reported to the police. We found that almost one third of our respondents had been victimized on the bus or at the bus stop during the past five years. “It felt like I was drowning,” said a young African-American woman who described how a thief had grabbed and cut a golden chain from her neck. “You always have to keep your eyes wide open here,” exclaimed a Latino man. Half the respondents reported feeling unsafe and “always on guard” while waiting for the bus. Those feelings were more prominent among women passengers, who said they felt tense and under siege, wishing they could see behind themselves, as their anxiety levels rose until the bus finally arrived.

We found these ten high-crime bus stops have none of the elements that might mark their space as “defensible.” All are situated in seedy and litter-filled commercial areas. Their surrounding environment is derelict and forbidding. Most are not visible from surrounding shops and lack adequate lighting. Empty lots and vacant, dilapidated buildings adjoin many of them. Desolate settings lacking either formal or informal surveillance make them attractive to criminals bent on committing crimes unnoticed.

Our data indicate that most serious crimes take place in isolated situations. A close examination of the immediate environment reveals a number of possible hiding places where potential criminals can easily hide to prey on their victims. Nearby alleys and empty lots offer perpetrators easy and varied escape routes. “These people are smart,” a police officer told us, referring to criminals who prey at bus stops. “They wear two shirts; they wear another pair of sweats over their pants. They’ll run into the alley, tear off their first layer, and walk out of the alley like nothing happened.”

While bus stops plagued by serious crime are desolate, stops with a high incidence of pickpockets and petty thefts are over-crowded. Overcrowding tends to happen at busy street corners, where multiple bus lines converge. In such situations many “eyes on the street” do not seem particularly helpful, as criminals easily blend into the crowd.

Criminologists argue that specific land uses are more likely to generate, or at least allow, crime than others; this has led them to identify certain negative land uses. This may be a controversial view, but we found evidence to support it. For example, bars and liquor stores are located close to eight of the ten most dangerous bus stops. While some of these liquor stores provide the only outlet for groceries in inner-city neighborhoods, we can’t ignore studies showing that consumption of alcohol can induce aggression and increase one’s willingness to take risks. Check-cashing facilities and pawn shops are also near high-crime bus stops. These  businesses often substitute for banks and, because they deal in large cash transactions, their customers offer likely targets for criminals. “Hot- sheet” motels, adult bookstores, and porn movie theaters are also common near high-crime bus stops. High concentrations of these businesses, combined with dilapidated buildings and other signs of neglect, increase the perception of seediness.

businesses often substitute for banks and, because they deal in large cash transactions, their customers offer likely targets for criminals. “Hot- sheet” motels, adult bookstores, and porn movie theaters are also common near high-crime bus stops. High concentrations of these businesses, combined with dilapidated buildings and other signs of neglect, increase the perception of seediness.

Measuring the Effects of Environment

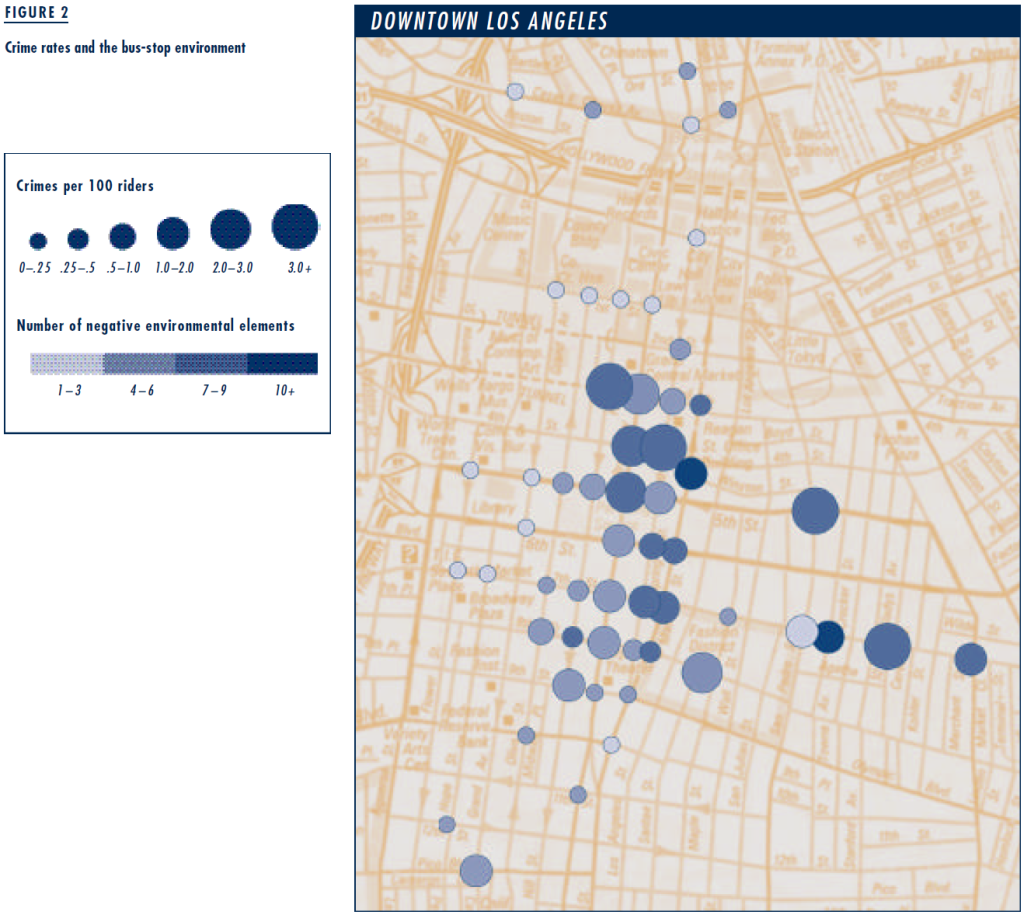

Qualitative and ethnographic data help portray the social traits of residents and riders who use high-crime bus stops. But we also need to understand how particular features of the physical environment relate to crime. So we also studied sixty high- and low-crime bus stops downtown in an effort to measure the effects of specific environmental variables. The map in Figure 1 displays the crime and ridership levels at the bus stops we chose for study.

Environmental indicators that we looked at include 1) urban-form characteristics of the surrounding area; 2) bus-stop characteristics; and 3) street characteristics. As we suspected, our analysis revealed that certain urban-form and bus-stop characteristics seem compatible with crime. For example, crime rates are higher at bus stops in areas with alleys and mid-block passages (corroborating the idea that crime is high where there are avenues for escape) and near multi-family housing, liquor stores, check-cashing establishments, vacant buildings, and buildings marked by graffiti and litter. When we narrowed the field to violent crimes only, we found that check-cashing establishments at bus stops have the strongest correlation with crime rates, followed by the presence of alleys.

Positive environmental factors include good visibility from surrounding establishments and the presence of bus shelters. Street characteristics such as on-street parking and vehicle traffic seem to affect crime rates. Intersections with on-street parking tend to have high rates, while heavy vehicular traffic is associated with lower crime rates.

More research is needed to expose the effects of variables that we’ve been unable to measure adequately. For example, counting light poles near bus stops during daylight hours has not allowed us to consider illumination levels from surrounding establishments, and our reluctance to conduct fieldwork at night in these unsafe locations has kept us from checking to see whether streetlights were working properly. We measured pedestrian traffic at only one time during the day for each bus stop, even though this is likely to be an important variable.

What Can Be Done to Make Bus Stops Safer?

Our data are clear evidence that environmental settings affect crime at bus stops. Because stops in close proximity, along the same bus routes, and presumably with passengers having the same socio-demographic characteristics are marked by  different crime rates, we conclude it’s the microenvironments that matter. In turn, that implies an array of policy and design options, some very simple, that can complement policing and thus improve safety.

different crime rates, we conclude it’s the microenvironments that matter. In turn, that implies an array of policy and design options, some very simple, that can complement policing and thus improve safety.

Unlike railway stations, bus stops are not permanently fixed in the urban landscape. They can be moved up or down the street as prudence requires. Moving bus stops away from undesirable establishments, multiple escape routes, and desolately empty spaces is imperative for passengers’ safety. Opportunities for crime can be reduced by eliminating niches where individuals wait in hiding and where isolated alleys offer escape routes. The general upkeep and cleanliness of the immediate public environment of the bus stop sends the signal that “someone cares.” Appropriate shelter design and good siting of a bus stop near open-front retail establishments can increase surveillance. In situations of extreme crowding, widening or extending sidewalks at the bus stop can decrease pedestrian congestion and reduce opportunities for purse and jewelry snatching. The retrofit of bus stops with shelters and lighting can make waiting for the bus more comfortable, less anxious, and safer.

For all these to happen, however, transit companies have to admit that the bus stop wait is a significant part of the overall transit system. They should target resources for the safety of their patrons by improving and maintaining the public environment at places where their buses stop.

Further Readings

Patricia L. Brantingham and Paul J. Brantingham, “Nodes, Paths, and Edges: Considerations on the Complexity of Crime and Physical Environment,” Journal of Environmental Psychology, v. 13, pp. 3–28, 1993 .

Ned Levine, Martin Wachs, and Elham Shirazi, “Crime at Bus Stops: A Study of Environmental Factors,” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, v. 3:4, pp. 339–361, 1986.

Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, “Hot Spots of Bus Stop Crime: The Importance of Environmental Attributes,” Journal of the American Planning Association, v. 65, no.4, 1999 .

Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, Robin Liggett, Hiro Iseki, and William Thurlow, “Measuring the Effects of Built Environment on Bus Stop Crime,” Working Paper, 1999. UCTC No. 419

Adele Pearlstein and Martin Wachs, “Crime in Public Transit Systems: An Environmental Design Perspective,” Transportation , v. 11, pp. 277–297, 1982.

Gerda We kerle and Carolyn Whitzman, S a f e Cities: Guidelines for Planning, Design and Management (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1995).

James Q. Wilson and George L. Kellig, “Broken Windows: The Police and Neighborhood Safety,” Atlantic Monthly, no. 249 (3), pp. 29–38, 1982.