As California grows, increased travel from more households, business activity, and goods movement will surely increase greenhouse gas emissions, lead to more congestion and air pollution, and damage ecosystems and neighborhoods—unless we change the basics of travel in California. We need to take action now to deliver a sustainable transportation system that provides the mobility and accessibility necessary for a prosperous economy, and to find ways of doing so that also assure a healthy environment, social equity, and a high quality of life. Here are some ideas for managing, improving, and reworking our urban transport systems that are proven best practices and, with legislative leadership, could be more widely utilized.

Urban Transportation Systems: The Context

For many decades, in the US and elsewhere, growth has been associated with increasing use of motor vehicles and increasing vehicle miles of travel. Even if current high fuel prices and economic woes moderate VMT increases, population growth in California will continue to push VMT upward. In addition, the private automobile totally dominates travel. For the journey to work, arguably the most transit-amenable trip, less than three percent of California’s workforce uses transit. Similarly small shares of the populace walk or bike to work on a regular basis. For other trip purposes such as shopping, the auto is even more dominant. In most areas fewer than one percent of non-work trips are on transit and only a few percent are on foot.

The car provides door-to-door service, protection from the elements, and speeds higher than the competition, even during congested periods.

The most obvious reason that auto use is prevalent is that for most trips, it is by far the most convenient means of travel. For most of us, the car provides door-to-door service, protection from the elements, and speeds higher than the competition, even during congested periods. Another reason for auto dominance is that single-use, low-density land development creates conditions where distances are too long for walking or biking to be practical, and demand is too low to justify intensive transit services.

Critics also point out that the automobile has been under- priced. Motorists cover only some of the costs of the streets and highways they use and do so indirectly, so that the costs are hidden (e.g., through developer exactions or sales taxes rather than gas taxes or other user fees.) As Donald Shoup has often pointed out, “free” parking supports considerably more auto use than would occur if parking were priced to recover its costs. In addition, the costs of air pollution, noise, habitat disruption, water pollution from runoff, greenhouse gas emissions, auto-related deaths and injuries, and congestion and delays are either externalized completely or are only partially covered by auto users. Certainly the under-pricing of auto use has led to over-subscribed roads and highways, but with nearly everyone dependent on autos for transportation, changing direction is both politically difficult and could have some unintended effects on social equity and the economy. However there are increasing reasons to search for a new direction. With half of California’s greenhouse gases coming from transportation, over four-fifths of that from urban travel, meeting the state’s climate change targets will be difficult unless a new paradigm emerges. More energy efficient cars and low carbon fuels will certainly have to be a big part of the shift, but it is unlikely that either will be sufficient to achieve climate stabilization targets in the time available. Nationally, a recent study by the Center for Clean Air Policy estimated that even with an aggressive expansion of low-carbon-emitting vehicles, CO2 emissions will still increase by forty percent between 2005 and 2030 due to more and longer motorized trips. That is, VMT increases will swamp the effects of cleaner-fuel technologies. Therefore demand management must be considered the complement to new technologies.

VMT increases will swamp the effects of cleaner-fuel technologies.

Innovative Partnerships to Reduce Transport Demand

As part of a broader agenda for advancing sustainable transportation solutions, more aggressive demand-side initiatives are needed. An important point here is that demand management covers a wide range of strategies, allowing measures to be matched to specific needs and opportunities. For example, strategies for managing demand can range from greater use of time scheduling (e.g., flextime, four-day workweeks, telecommuting) to expanded mobility options (transit pass programs, carsharing, shuttle services) to pricing strategies (congestion pricing, carbon fees, parking fees) to coordinated land use/transport planning (pedestrian- friendly communities, transit-oriented development). The central idea is to make more efficient use of scarce resources, be they fuel supplies, clean air, or peoples’ time, by shifting demand by hours of the day, modes of travel, and locations of urban activities.

As part of a broader agenda for advancing sustainable transportation solutions, more aggressive demand-side initiatives are needed. An important point here is that demand management covers a wide range of strategies, allowing measures to be matched to specific needs and opportunities. For example, strategies for managing demand can range from greater use of time scheduling (e.g., flextime, four-day workweeks, telecommuting) to expanded mobility options (transit pass programs, carsharing, shuttle services) to pricing strategies (congestion pricing, carbon fees, parking fees) to coordinated land use/transport planning (pedestrian- friendly communities, transit-oriented development). The central idea is to make more efficient use of scarce resources, be they fuel supplies, clean air, or peoples’ time, by shifting demand by hours of the day, modes of travel, and locations of urban activities.

Public-private partnerships can be a key approach for each of these strategies. For example, public-private partnerships that invest in and encourage commuting by transit, carpool, bike, and foot could transform transportation opportunities for commuters. Employers, commercial building managers, office park developers, and organizations funded by these private sector groups would work with employees to support commuting by public transport, company buses, carpooling, cycling, or walking. Cities could also allow these same organizations to follow flexible parking standards—i.e., to provide fewer spaces—when adopting these other enhanced mobility options. A lower parking requirement would be a cost savings that could help fund alternative modes. It would also make housing more affordable for those who opt to live near transit stations, increasing transit ridership in the process.

A lower parking requirement would be a cost savings that could help fund alternative modes.

Private partners could introduce such measures as deep- discount or free transit passes, shuttles to and from transit stops and other important destinations, commute allowances, and pricing parking to rebalance commute options in favor of more sustainable modes of travel. They could offer private shuttles to bring their employees to work and home again. They could make carsharing available to employees for midday trips and emergency travel, reducing their need for cars. These measures would reduce total demand and thus lower greenhouse gas emissions, congestion, and other traffic problems, while maintaining good access and mobility for the travelers. While more pro-active employer participation might be rewarded by a more productive workforce, for other private interests, direct financial incentives might be necessary to prod them into action. Carbon credits or corporate tax write-offs are two possible examples.

While private sector actions could make important contributions on their own, and deserve support for that reason, far more could be accomplished by coordinating public sector investments with private sector initiatives. For example, public agencies could invest in transportation improvements that would make transit use, carpooling, and walking excellent choices for commuters. Promising measures would include priority treatment for transit and other high-occupancy vehicles, high frequency and direct or express transit services to major employment centers, and high- quality bike and pedestrian networks linking employment centers to transit stations, restaurant districts, residential areas, and other desired destinations. On the land-use front, governments can also lead by example in many ways: for instance, by siting public offices near transit stations, or by following the lead of the state of Maryland, which offers “Live Near Work” relocation allowances and financial incentives for civil servants.

Public-sector partners could further reward high-performance employment centers—for example, those that achieve at least 25 percent of their work travel by modes other than drive-alone—by funding part of the cost of the workplace-based programs. Over time, as transit and other commute alternatives improve and rider- ship grows, targets for performance could be stepped up and rewards increased (consistent with increasingly rigorous targets for greenhouse gas reduction.) Similarly, local governments could offer credits and offsets against impact fees and exactions for projects in walkable, mixed-use communities and locations well-served by public transit—i.e., the kinds of places that reduce vehicle trips and thus relieve the need for expanding road capacity.

Successful examples of employer-based programs abound in the Bay Area—Google’s far-reaching employee shuttles, Bishop Ranch’s award-winning commute alternatives program, UC Berkeley’s deep-discount transit passes for students and employees, and dozens of companies that offer shuttles to get employees the “last mile” from the transit station to the workplace and back again. Companies also provide commute allowances and/or parking cash-out (the funds can be used to pay for parking, transit passes, or a new bike for commuting), offer non-drivers guaranteed rides home in case of emergencies, and, increasingly, participate in carsharing programs so employees have access to a car when they need one without having to drive theirs to work.

Community partnerships could help visitors, hotel guests, and community residents get to transit all day long, as well as get employees to work in the morning and help everyone travel to restaurants, gyms, doctor’s appointments, or shopping.

As another option, employers and local governments could run shuttles jointly, not just for employees but serving other community residents as well. Community partnerships could help visitors, hotel guests, and community residents get to transit all day long, as well as get employees to work in the morning and help everyone travel to restaurants, gyms, doctor’s appointments, or shopping. The Emeryville-Go-Round, a free shuttle paid for by employers, hotels, and retail establishments, is an example. Employers are also key implementers for flextime and telecom- muting, as a way to reduce travel at peak times and throughout the day. Local governments could work with major employers to help them adjust work schedules in coordination with additional or shifted public transit schedules. They could also seek to more evenly spread the days of the week when employees on four-day work schedules work at home.

By rewarding success in such programs with public investments targeted to make them even more effective, the public sector would forge a valuable partnership for transportation sustainability. By giving California travelers top-quality travel alternatives and incentives for using them, particularly during congested commute periods, we can go a long way toward achieving sustainability goals.

Getting the Price for Transport Services

Transportation bottlenecks in the state’s large metropolitan areas threaten our economic competitiveness, but our pricing strategies for transportation provide no incentive for more efficient use. Our cents-per-gallon gas taxes, same-price-all-day bridge tolls, and flat-rate (or free) parking spots hide the true costs that heavy auto use imposes—in time, money, and community and environmental damage—especially in the congested peak periods.

Getting the price right while maintaining mobility and access for everyone is not easy, but it is proving to be an increasingly important strategy across the US and abroad, as shown by experiences with congestion pricing in Stockholm, London, and Singapore. Charging more for peak period travel not only reflects its true higher cost, it also generates funds needed to improve transport facilities (roads, transit, and other commute alternatives). In fact, this is one of the few strategies that can both help tame congestion and raise the revenues needed to offer good alternatives and offset the cost for low-income travelers.

Experiences with HOT lanes in California, notably SR 91 in Orange County and I-15 in San Diego, show these facilities are hardly “Lexus Lanes,” instead being used by people of all income levels as needed, such as when running late for work or when personal stress is high.

Three strategies are increasingly being implemented across the US and abroad: high occupancy/toll (HOT) lanes, parking pricing, and cordon pricing. HOT lanes help vans, shuttles, buses, and carpools travel fast during peak periods, avoiding congestion; those solo drivers who are in a hurry could also use HOT lanes, paying tolls that not only help pay for the lanes themselves but also support commuter transit, shuttles, and carpools. Experiences with HOT lanes in California, notably SR 91 in Orange County and I-15 in San Diego, show these facilities are hardly “Lexus Lanes,” instead being used by people of all income levels as needed, such as when running late for work or when personal stress is high. Parking pricing, which could be implemented by both public and private sectors, might not only recover the costs of these expensive facilities but also generate funds to pay for commute alternatives and mitigate environmental problems from parking, such as water run-off. Finally, in certain highly congested districts and corridors, such as downtown San Francisco or the Livermore Pass, road pricing could help the many people who work and do business there travel faster and more reliably, with revenues from tolls going to support transit services not only in the city itself but in outlying counties.

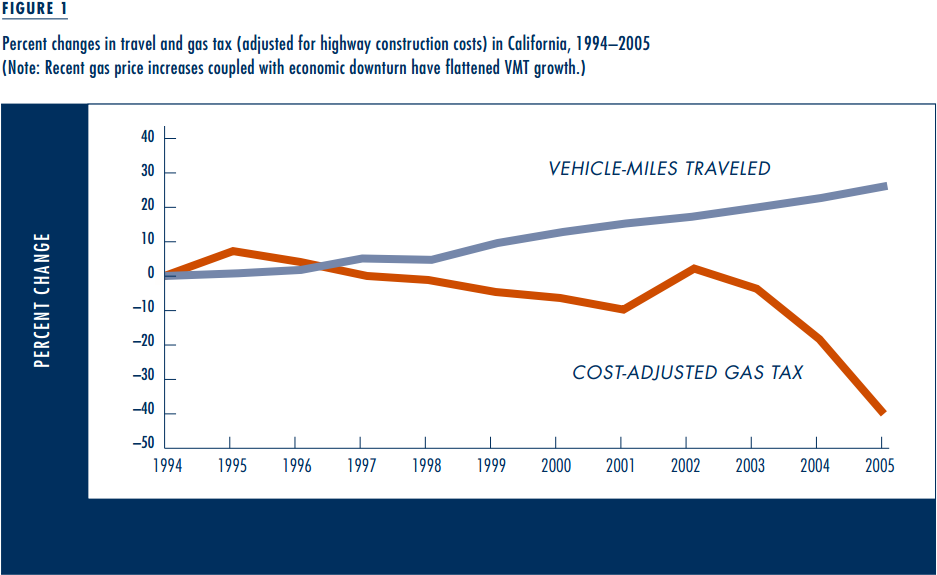

Pricing strategies could not only help moderate, reduce, or shift transportation demand, but also could help offset declining gasoline taxes. Fuel-efficient vehicles, while good news from an energy conservation and greenhouse gas perspective, will exacerbate transportation funding shortfalls as long as the gas tax is a fixed cents-per-gallon. Also, rapidly rising highway construction costs during a period of rapid increases in travel have dramatically eroded the purchasing power of gas-tax proceeds (Figure 1). The seriousness of this problem has finally been recognized at the federal level, but so far no clear policy direction has emerged from the commissions that have been studying options. An increase in the state gas tax could be coupled with other pricing strategies. Alternatives to consider are fees based on miles traveled using available GPS and information systems technologies, weight- distance fees for commercial vehicles (as currently practiced in Oregon), carbon taxes, and peak-period surcharges (for cars and transit).

While the equity implications of such fees certainly need to be evaluated, previous work makes it clear that sales taxes, which many counties have used to supplement their transportation revenues, are in fact far less equitable than other transportation pricing approaches. Sales taxes have also proven to be problematic in periods of economic downturn, when they decline sharply. Because they are not directly tied to transportation use, they provide no information to consumers about the costs of travel. Given the need to find new revenue sources for transportation, a serious evaluation of the economic, social, and environmental effects of different instruments is in order. Pricing strategies, we believe, should be toward or at the very top of revenue options considered by local and state leaders.

Integrated Transit Networks that Shape Regional Growth

Transit has maintained ridership but has lost mode share in most of the US. If transit systems are going to play a role in shaping California growth and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, they must be competitive and extensive. Conventional forms of transit don’t perform well in the low-density suburbs that characterize much of California’s growth. However, in at least some of these suburbs, lower-cost shared-ride services—such as community shuttles, shared-ride taxis, dynamic ridesharing, and electric- powered station cars—could serve a useful transit-like function or provide low impact access to transit stations.

Too often, transit is not given priority for road space in the cities and regions it serves.

Today, however, in much of the state, transit services are narrowly conceived and not well coordinated. Few transit agencies see their job as offering mobility services; instead they see them- selves as bus or rail operators. They have failed to offer a full range of services matched to markets. Transit agencies in adjacent districts or counties too often operate on uncoordinated schedules, with different hours of operation and different fare policies and payment media—a problem particularly magnified in the Bay Area, where 27 operators ply their trade. Transit agencies also have been stymied from providing the best possible service by the inaction of street and highway operators and local governments. Too often, transit is not given priority for road space in the cities and regions it serves. Buses are stuck in traffic instead of enjoying dedicated lanes and priority treatment. Transit routes and stations often lack the pedestrian and bike networks, bike parking, passenger shelters, and information systems that would make transit use faster, more convenient, safer, and more enjoyable. Where public transport offers a reliable, customer-service-oriented alternative to driving, it has been able to capture a substantial share of travel. Transit agencies and their partners must tackle the service/pricing/ institutional integration issues that limit transit effectiveness, or regional agencies should be given the mandate to step in and do so.

Coordinating Land Use and Transportation

While much can be done to manage demand through travel choices and pricing, the pattern of land use strongly shapes how transportation services are used, as well as what transportation services can be offered cost-effectively. The most basic strategy for changing travel behavior is to create more walkable communities. This means not only having safe and comfortable facilities for walkers—sidewalks and trails—but also places to go that are within walking distance. Cities planned with shopping and employment within walking distance of many residents will be more convenient, more sustainable, and healthier places than those that rely almost entirely on motorized travel.

Coordinating land use with transit investment allows for larger scale and higher density development and can shape a regional development strategy. Transit-oriented development, or TOD, has been proven to reduce travel by ten to forty percent compared to the auto-dependent single-use development patterns common in many suburban areas. The sizeable range reflects, among other things, the quality of transit service offered at the TOD, and the size and configuration of the TOD itself. In the case of the Montelena apartment complex near the Hayward BART station, a 2007 study found the average daily number of vehicles coming in and out of the project was 63 percent less than what the Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE) Trip Generation manual predicts. This is mainly because households that live in TODs, even when adjusting for income, tend to own fewer autos. This should be accounted for not only in setting parking codes but also in granting mortgages to home-buyers, since fewer outlays for owning and using a car frees up money for housing purchases.

Transit-oriented development, or TOD, has been proven to reduce travel by ten to forty percent compared to the auto-dependent single-use development patterns common in many suburban areas.

TOD reduces trips by providing moderate- to high-density housing, employment, and services within walking distance (ten to fifteen minutes) of a well-served transit station. Space is provided in the TOD for land uses that meet the TOD population’s daily needs (e.g. groceries, pharmacies, cafes and restaurants, banks, bookstores, clothing stores, office supplies, small offices) perhaps in the first floor of office buildings, perhaps in a Main Street shopping district. Special attention is given to making the TOD a comfortable and attractive place for walking, biking, and enjoying the urban environment, as well as a good place to catch a train or bus. Some people may choose to live and work in the same TOD; others will live there and use the TOD’s high-quality transit service to commute to work and elsewhere; still others use their cars for commuting but will walk around the TOD to shop, attend an event, or do business. Because it accommodates a mix of housing types and provides convenient, nearby services, TOD—if it is well planned—can simultaneously help meet housing needs for a variety of incomes, age groups, and life styles, including families, singles, and seniors; reduce auto dependence; create environmentally sound, economically robust, successful communities; and deliver riders to the transit system. It also enriches choices in living environments, something that is woefully in short supply in many of California’s suburbs and exurbs.

While in some places TOD takes decades to develop, the fast growth rate in California provides an advantage—the state can accommodate substantial amounts of our future growth in TOD. Also working on California’s side is its demographics, notably a large population of immigrant households, many from places with a heritage of transit-oriented living. However, TOD also faces barriers, including the higher costs and complexities of infill and mixed-use development. Impact studies that assume that, regard- less of location, all development will generate the same auto ownership rates (hence parking requirements) and the same auto trip generation (hence traffic impact fees) are also a substantial barrier and should be changed. Incentives to provide mixed-income housing in TODs are necessary so that TOD doesn’t become priced beyond the reach of the workers providing services there.

A few islands of TOD in a sea of auto-oriented development will fail to draw many Californians to trains and buses.

TOD also will be less effective if it is treated as “transit station exceptionalism” rather than a key strategy for regional development. Building a few mixed-income projects around TOD will increase housing and travel choices for some, but will not make a big difference in congestion, emissions, or greenhouse gas emissions if at the same time local jurisdictions continue to approve low-density single-use housing tracts scattered across the landscape. A few islands of TOD in a sea of auto-oriented development will fail to draw many Californians to trains and buses. International experiences, such as from Stockholm, Copenhagen, Tokyo, and Singapore, show that TOD works best when designed and coordinated along linear axes, forming a “necklace of pearls.” As regions in both northern and southern California expand beyond their traditional boundaries, either far more explicit and forceful inter- regional coordination or state intervention is needed to keep growth patterns sustainable and transit services effective.

Transit-Oriented Corridors: TOD as a String of Pearls

California has two major growth issues on which to focus. One is the role of metropolitan and intercity transport infrastructure— including both roads and possible high-speed rail investments— in shaping urbanization, especially in the Central Valley. The second area needing attention is the un(der)planned spillover of growth into agricultural areas and the Sierra foothills and deserts around the San Diego-LA and Bay Area-Sacramento “megaregions.” In both cases, the emerging growth patterns are tied to transportation investments, but are driven in large part by housing affordability and quality-of-life issues in existing cities. Unless it is well man- aged, growth in these areas could easily have serious negative impacts on the state’s waterscape, its native species, and its agriculture. Multi-sectoral coordination of planning, implementation, and state funding is urgently needed. Clearly, metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) currently lack the authority to manage growth that spills well beyond their boundaries but nonetheless affects their traffic, environmental quality, and economic well-being. Pro-active action at the state level is needed. The current Blueprint planning efforts taking place around the state are a good start, but they must be tied to performance measures and implementation mandates if they are to be truly effective.

California has two major growth issues on which to focus. One is the role of metropolitan and intercity transport infrastructure— including both roads and possible high-speed rail investments— in shaping urbanization, especially in the Central Valley. The second area needing attention is the un(der)planned spillover of growth into agricultural areas and the Sierra foothills and deserts around the San Diego-LA and Bay Area-Sacramento “megaregions.” In both cases, the emerging growth patterns are tied to transportation investments, but are driven in large part by housing affordability and quality-of-life issues in existing cities. Unless it is well man- aged, growth in these areas could easily have serious negative impacts on the state’s waterscape, its native species, and its agriculture. Multi-sectoral coordination of planning, implementation, and state funding is urgently needed. Clearly, metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) currently lack the authority to manage growth that spills well beyond their boundaries but nonetheless affects their traffic, environmental quality, and economic well-being. Pro-active action at the state level is needed. The current Blueprint planning efforts taking place around the state are a good start, but they must be tied to performance measures and implementation mandates if they are to be truly effective.

Policies and Recommendations

While urban growth in California faces major challenges, growth also provides an opportunity to reshape cities and regions for a more sustainable future. The need to reduce greenhouse gases and maintain global competitiveness means that new directions must be found, including new technologies for transport, but going well beyond that to demand management and greater coordination of transportation and urban development. Innovative public-private partnerships for commuting and beyond, the use of pricing for parking and road use, improved transit coordination and services, investment in transit-oriented development, and better management of growth associated with new transportation infra- structure are important strategies for reducing total travel demand without reducing access and mobility. Directing discretionary funds toward these ends would be a start. Specific actions that could be funded with current and future revenues and supported with legislation include the following:

- Providing new incentives and rewards for employers and private sector managers to implement flexible parking, employer shuttles and other mobility options, flextime, and

- Granting MPOs and congestion management agencies and cities the authority to test and evaluate road pricing and tolling in those areas and corridors where public support for such actions can be developed— and possibly funding pilot

- Establishing benchmarks for transit performance, with funding and technical assistance tied to meeting the initial benchmarks and then to improving them; encouraging coordination among adjoining transit districts, employers, and

- Assisting local governments and transit agencies to design land use plans, zoning, ordinances, and building codes for TOD; providing funding for hard-to-finance pre-development costs for TOD plans, coordinated with affordable housing

- Taking a leadership role in coordinating urban development around high speed rail and other major intercity transport

- Creating a stronger institutional framework for managing growth in the Central Valley and Sierra foothills.

Further Readings

G. Binger, R. Lee, Charles Rivasplata, A. Lynch, and M. Subhashini. Connecting Transportation Decision Making with Responsible Land Use: State and Regional Policies, Programs, and Incentives (San Jose: San Jose State University, Mineta Transportation Institute, 2008).

Robert Cervero, “California’s Transportation Problems as Land- Use and Housing Problems: Towards a Sustainable Future,” in California’s Future in the Balance: Transportation, Housing/Land Use, Public Higher Education, and Water Four Decades Beyond the Pat Brown Era, A. Modarres and J. Lubenow, eds., The Edmund G. “Pat” Brown Institute of Public Affairs, California State University, Los Angeles, 2002.

Elizabeth Deakin, “Transportation in California: The Coming Challenges,” in California’s Future in the Balance: Transportation, Housing/Land Use, Public Higher Education, and Water Four Decades Beyond the Pat Brown Era, A. Modarres and J. Lubenow, eds., The Edmund G. “Pat” Brown Institute of Public Affairs, California State University, Los Angeles, 2002.

Reid Ewing, Keith Bartholomew, Steve Winkelman, Jerry Walters, and Don Chen. Growing Cooler: The Evidence on Urban Development and Climate Change. (Washington, D.C.: Urban Land Institute, 2008.)

H. Lund, Richard Willson, and Robert Cervero, “A Re-Evaluation of Travel Behavior in California TODs,” in Journal of Architecture and Planning Research, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 247–263, 2006.