The most ambitious proposal for transportation planning ever considered for the San Francisco Bay Area—the Golden Gate Authority—went down in defeat in 1962, bringing serious efforts for regional government to an end. Authority advocates touted its potential to promote prosperity, provide employment, and relieve congestion, promises that appealed to many Bay Area leaders and interest groups. However, the prospect of a powerful new transportation authority also garnered strong opposition.

In the decades following World War II, policy analysts and public officials throughout the United States recognized the need to address various problems created by rapid metropolitan growth, including traffic congestion. A virtual policy consensus created a rare window of opportunity to establish new institutions to govern and plan on a regional scale. Proponents of the Golden Gate Authority believed that the agency could centralize transportation policy and eventually provide comprehensive planning for the entire nine-county region. The story of the Authority’s failure suggests that the patchwork pattern of decentralized, fragmented government in most American metropolitan areas may be self-perpetuating, with important implications for future efforts to plan and coordinate metropolitan area development.

For Metropolitan Problems, a Metropolitan Solution

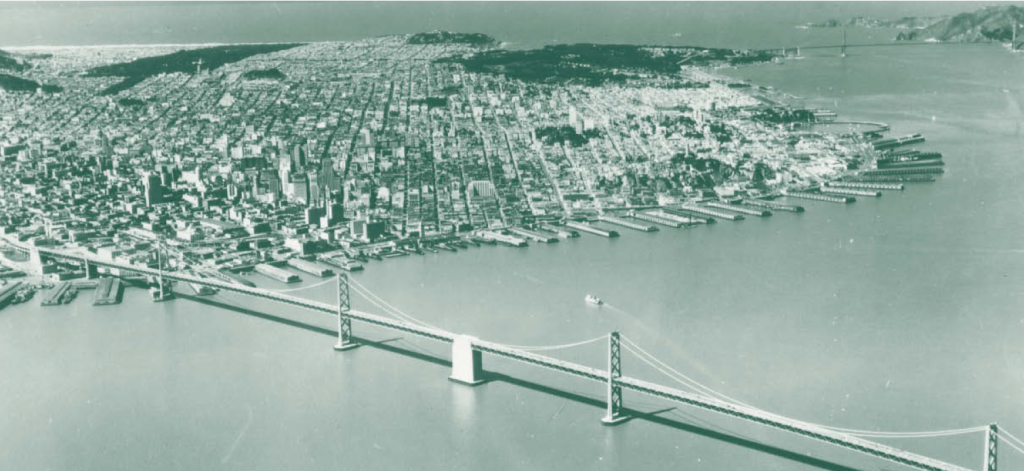

The Bay Area population more than doubled between 1940 and 1960, and the number of automobiles more than tripled. Commuters packed both the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge and the Golden Gate Bridge. Moreover, interregional and international transportation facilities were under severe pressure. Three airports suffered from congestion, five major ports competed for traffic, and all of them were out of date. By the mid-1950s state analysts concluded that inadequate and uncoordinated transportation facilities were hindering development in the region.

The proposed Golden Gate Authority represented the culmination of years of planning by the Bay Area Council (BAC), the region’s most powerful civic association representing big business, industry, and labor. The BAC’s new president, Edgar Kaiser, led the effort, along with State Senator Jack McCarthy of Marin, who was also chairman of the state Committee on Metropolitan Bay Area Problems. They were an energetic team—a young, ambitious politician partnered with a scion of industry eager to make his mark.

New transportation infrastructure would be financed with revenue bonds, reducing the need for state or federal subsidies and therefore limiting outside interference and the need for political negotiations.

At Kaiser’s behest, the BAC hired Coverdale & Colpitts, a prominent consulting firm based in New York, to develop a detailed proposal for the Golden Gate Authority and to make a case for its value. Their report, describing an independent public corporation, was released to the public in December 1958. The proposed Authority would have a corporate management structure, giving “a business administration to what are essentially business functions,” according to the consultants. Following the recommendations of local chambers of commerce, county supervisors would appoint the Authority’s leadership. Appointees would head the agency, but a professional staff would be expected to guide policy based on the “facts of growth,” thus reflecting the backers’ faith in expert administration and engineering objectivity. Financial independence was critical in this plan. New transportation infrastructure would be financed with revenue bonds, reducing the need for state or federal subsidies and therefore limiting outside interference and the need for political negotiations. The staff members would acquire and administer major revenue-generating transportation facilities, and use these assets to finance a wide variety of new projects.

At Kaiser’s behest, the BAC hired Coverdale & Colpitts, a prominent consulting firm based in New York, to develop a detailed proposal for the Golden Gate Authority and to make a case for its value. Their report, describing an independent public corporation, was released to the public in December 1958. The proposed Authority would have a corporate management structure, giving “a business administration to what are essentially business functions,” according to the consultants. Following the recommendations of local chambers of commerce, county supervisors would appoint the Authority’s leadership. Appointees would head the agency, but a professional staff would be expected to guide policy based on the “facts of growth,” thus reflecting the backers’ faith in expert administration and engineering objectivity. Financial independence was critical in this plan. New transportation infrastructure would be financed with revenue bonds, reducing the need for state or federal subsidies and therefore limiting outside interference and the need for political negotiations. The staff members would acquire and administer major revenue-generating transportation facilities, and use these assets to finance a wide variety of new projects.

Bridge tolls—which would be the Authority’s greatest financial resource—were essential to the agency’s independence and efficacy. Bay Area bridges, together worth $225 million in 1957 ($1.8 billion today), represented nearly 60 percent of the Authority’s potential assets. The Golden Gate Bridge and the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge (which Kaiser dubbed the “Great Fat Golden Cow”) had large surpluses, and together would generate nearly 80 percent of all projected Authority revenue. The California Toll Bridge Authority, a state agency that answered to a legislature and a governor who supported the proposed Golden Gate Authority, controlled all but one of the region’s bridges. The Golden Gate Bridge was the exception: it was operated by an independent, special-purpose agency, the Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District.

The consultants designed the Golden Gate Authority to evolve and expand beyond transportation, as Kaiser put it, to “plan for the further development of the Bay Area, not only upon economic and industrial lines, but also . . . to provide residential, recreational and social facilities of value to all citizens.” The Coverdale & Colpitts report presented a vision of regional planning in which an independent agency would be empowered to pursue the intensive development sought by Bay Area business and civic elites.

In a press conference following the release of the report, Kaiser praised BAC leaders for accepting their “proper leadership role” by supporting the new regional authority. In the following months, BAC members spoke throughout the Bay Area, and both Kaiser and McCarthy stumped relentlessly. Kaiser also met with the editors of major newspapers who immediately endorsed the proposal, and in February 1959, BAC allies introduced legislation in Sacramento to create the Golden Gate Authority (Figure 1).

Defending Local Autonomy

Opposition to the Golden Gate Authority came almost exclusively from local governments. In an attempt to protect their autonomy, officials of cities, counties, and special districts asserted the intrinsic value of home rule.

Berkeley Mayor Claude Hutchison called a meeting to discuss the Golden Gate Authority in March 1959. Mayors, councilmen, and city managers representing 42 cities and counties attended. The California League of Cities representatives emphasized the importance of local self-determination and opposed any kind of master plan. San Leandro City Manager Wesley McClure offered a scathing critique of the proposed Authority: “It is . . . not merely a monster, but a financially healthy monster, which, with built-in financing from all the lucrative revenue producing facilities of the area, can independently go its merry way . . . without regard [for] local government.” Kaiser attended with a prepared speech in hand, but never got a chance to speak.

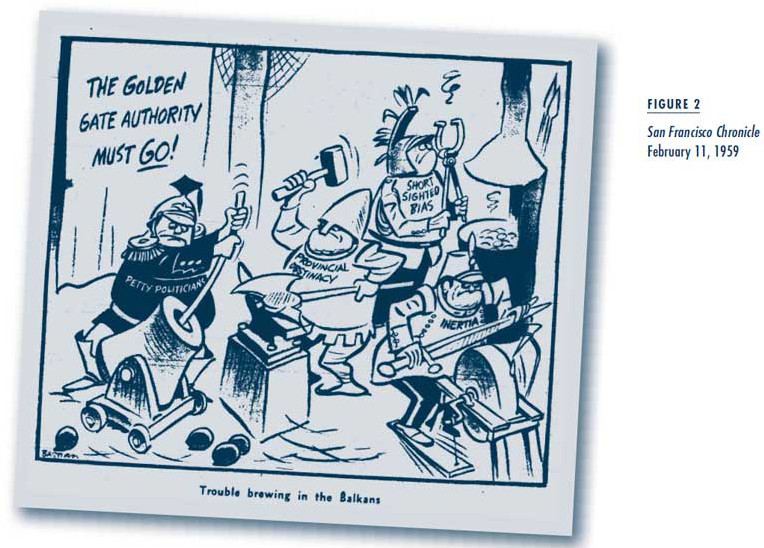

Attendees passed a resolution requesting that the state legislature delay the bill and formed a new organization to oppose it. The resulting Planning Committee on Metropolitan Bay Area Problems met regularly over the next several months. From this seed of reaction a council of governments grew, intended to derail the proposed Authority by serving as an alternative institution for regional planning (Figure 2).

The other major opponent of the proposed Authority was the Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District. The agency had a reputation as a well-funded bastion of patronage and perquisites, and its directors resolved to defend it. Its general manager made use of a generous expense account to lobby legislators in Sacramento. Directors campaigned around the Bay Area and convinced Sonoma, Mendocino, and Napa counties to oppose the Authority.

The [Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District] had a reputation as a well-funded bastion of patronage and perquisites, and its directors resolved to defend it.

Golden Gate Bridge representatives also convinced San Francisco supervisors that the Authority would undermine their influence over transportation policy and result in higher tolls. After months of discussion, the supervisors called for nine amendments including a guarantee that they would appoint half of the Golden Gate Authority’s directors. This was a deal-killer; Alameda County in the East Bay had about the same population as San Francisco, and Oakland’s leaders would never agree to let their biggest rival dominate.

During the 1959 legislative session, state lawmakers added more than a hundred amendments to the bill in an attempt to answer all local objections to the Authority. By the time Governor Pat Brown went on record in favor of creating the Authority, it was already too late. San Francisco Chronicle editors commented that “the demise of the Authority proposal—as amended and reamended by the Legislature—may prove a mercy killing…. [It] was so thoroughly emasculated in terms of representation, of power, function and duty, that enactment might have created more problems than it solved.”

Hearings in the Bay Area

Following this defeat, Golden Gate Authority proponents geared up for a new effort in 1961. At end of the 1959 legislative session, the Legislature created a study commission made up of Authority supporters. Twelve public hearings revealed that the Authority could easily acquire most transportation facilities, including ports and airports in Oakland, Redwood City, San Jose and San Francisco. Overall, testimony was positive and suggested strong public support. Most objections came from local officials who were concerned about the terms of acquisition for individual facilities. The California Director of Public Works remarked that the Authority should not be compromised by petty local protests and pledged to support the transfer of state bridges to the Authority.

The most contentious hearings revealed that Golden Gate Bridge officials opposed the Authority most resolutely. George Anderson, an elderly director who had promoted the bridge in the 1920s, read a lengthy statement against the Authority. He cited the rights of the bridge’s original bondholders and the reduction (or elimination) of representation for bridge district counties as reasons to oppose the bill. When asked hostile questions by commission members about the bridge district’s large staff, well-paid executives, and costly maintenance, however, he offered no real defense. Commissioners also pointed out that none of the bridge district’s large reserve funds or surplus revenue was being reinvested, and made it clear that they were determined to take over the bridge and use its tolls for regional development.

The San Francisco Examiner followed the hearings with a three-day series detailing extravagance and waste at the Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District. Undeterred by negative publicity, bridge district officials continued their fight. One radio commentator remarked: “It seems likely that the district directors feel that they have built up a tidy little empire and, by gum, they don’t want to let it go.”

The San Francisco Examiner followed the hearings with a three-day series detailing extravagance and waste at the Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District. Undeterred by negative publicity, bridge district officials continued their fight. One radio commentator remarked: “It seems likely that the district directors feel that they have built up a tidy little empire and, by gum, they don’t want to let it go.”

In the meantime, local government officials who opposed the Authority developed an alternative proposal for regional government. At the final hearing, Berkeley Mayor Claude Hutchison introduced a proposal for an Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG). The organization would be comprised of a single representative from each city and county. Its members would discuss problems and develop recommendations, but would have no power to take any action. Authority advocates were immediately antagonistic to ABAG. Economist Thomas Lantos pointed out that the creation of ABAG would contradict one of the basic goals of the proposed Authority, “to curb the [influence] of cities and counties in regional matters.” In addition, Lantos objected that ABAG’s representation would have no relationship to population, and would represent the interests of governments rather than people. Hutchison responded that ABAG’s lack of power made representation immaterial. Although his toothless proposed association garnered ridicule from the commission members, he nevertheless began enrolling members.

Overall, the hearings represented a success for Authority proponents. The counties of Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, San Francisco, San Mateo, and Solano all went on record supporting the Authority. Editors of all major Bay Area newspapers endorsed it as well. The Senate bill had backing from 25 authors (out of 40 Senators), including most of the Bay Area delegation. By all indications, public opinion, as well as the majority of the state legislature, supported the Golden Gate Authority.

Local Interests versus Regional Planning

One Marin County commentator predicted that, as the effort for a regional agency intensified, “the [Golden Gate] bridge folks will come out swinging.” And indeed, the bridge directors expanded their public campaign against the Golden Gate Authority. It was their behind-the-scenes activities in Sacramento, however, that ultimately paid off.

The Senate Transportation Committee had to approve the new Golden Gate Authority bill before it could go to the Legislature for a vote. State Senator Randolph Collier, who represented the smallest bridge district county, on the Oregon border, chaired the committee. Known as the “silver fox of Sacramento,” Collier was a major advocate for state highway construction. He also had a direct interest in the Golden Gate Bridge. Not only was Del Norte County’s right to appoint a Golden Gate Bridge director a rare sinecure for Collier’s small rural district, but his constituents also had large contracts for bridge advertising and public relations. Politically, he needed to defend those benefits. In addition, Collier’s consistent and effective defense of bridge district interests in Sacramento were no doubt well-rewarded from the agency’s large budget for lobbying and campaign contributions.

Not only was Del Norte County’s right to appoint a Golden Gate Bridge director a rare sinecure for Collier’s small rural district, but his constituents also had large contracts for bridge advertising and public relations.

On provincial grounds, Collier objected that the proposed Golden Gate Authority would “take millions of dollars of state property and turn it over, [giving] no one in the rest of the state any voice in the matter at all.” When committee hearings commenced, Collier welcomed bridge defenders testifying against the Authority. He refused to limit the length of presentations against the bill or to allow hostile questioning, repeatedly cutting off McCarthy, a member of the committee. Some proponents of the bill appeared three times before they were heard and many never spoke at all.

After two weeks of testimony, a six-to-six committee vote effectively killed the bill. The result suggested careful orchestration: if it had been defeated outright, it could have been reintroduced. Instead, the committee scheduled more hearings. An Assembly version of the bill passed easily, 54 to 14. It clearly had sufficient support to pass in the Senate as well, but it never made it out of Collier’s committee (Figure 3).

After two weeks of testimony, a six-to-six committee vote effectively killed the bill. The result suggested careful orchestration: if it had been defeated outright, it could have been reintroduced. Instead, the committee scheduled more hearings. An Assembly version of the bill passed easily, 54 to 14. It clearly had sufficient support to pass in the Senate as well, but it never made it out of Collier’s committee (Figure 3).

Editors of the San Francisco Chronicle and Examiner blamed Senator Collier and “imperial” Golden Gate Bridge directors for the defeat, and pointed out that the representatives who opposed the Authority represented only 900,000 people while its supporters spoke for nearly nine million.

Bridge district officials honored Collier after the close of the 1961 session with a “victory dinner.” He had defended local government by using his Senate committee to defy Sacramento’s ruling majority as well as the Bay Area delegation. The state legislature, always a blunt instrument, could more easily obstruct change than facilitate it.

Kaiser finally conceded defeat in 1961, but cited public support for the Golden Gate Authority as evidence that regional cooperation could still prevail. Pragmatically, he also announced that the BAC would endorse ABAG. Kaiser recognized that, although it was intentionally designed to undermine regional planning, ABAG was now the only means of providing it.

ABAG’s structure and rules served the interests of the local government officials who created it. ABAG could only “study metropolitan area problems” and make recommendations. Yet, its existence thwarted attempts to create any more authoritative regional entity. When the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) was created to fulfill federal planning requirements in 1971, it was similarly powerless, lacking the resources or initiative to shape regional transportation in any meaningful way.

At the time of its creation, ABAG was one of seven regional councils of governments (COGs) in the United States, but by 1972 there were more than three hundred. Like ABAG, many prevented more authoritative agencies from infringing upon local sovereignty as new regional planning requirements were introduced in the 1960s. Among planning advocates, COGs became notorious obstacles, serving as local government bulwarks against outside interference. Their lack of power was fundamental to their purpose.

Conclusion

The window of opportunity to create meaningful regional government closed in the 1970s, both in the Bay Area and around the country. Ideological and intellectual change resulted in growing support for decentralization and market-based governance. But a half-century later, scholars and policy analysts are again advocating for regional coordination and planning. New imperatives will no doubt inspire and create opportunities for metropolitan area regionalism in the 21st century, especially if federal and state governments continue to falter. However, the defeat of the Golden Gate Authority suggests that decentralized governmental structures represent a formidable obstacle to reform. In the Bay Area, the collective resistance of local governments thwarted a popular proposal backed by a unified civic elite, thus demonstrating the power of local governments.

The BAC designed the Golden Gate Authority to promote the interests of big business and industry, and the proposal had significant shortcomings. Nevertheless, the capacity to shape transportation and other policies at the regional level in order to address economic, social, and environmental problems was and remains critical for sound metropolitan area development and competitiveness. While Golden Gate Authority backers were able to rally political and public support, they were unable to effectively navigate the complex decision-making process in Sacramento or to counter behind-the-scenes obstructionism in the Bay Area.

The capacity to shape transportation and other policies at the regional level in order to address economic, social, and environmental problems was and remains critical for sound metropolitan area development and competitiveness.

More recently, strategies for regional reform have sought to ameliorate local opposition by reducing the authority and scope of proposed new agencies. However, local governments are never likely to voluntarily compromise their autonomy or to acquiesce to authoritative regional government. Regional planning advocates might achieve better outcomes by focusing on overcoming structural obstacles and defeating their opponents than by weakening their proposals for regional governance.

Further Readings

Louise Nelson Dyble. 2009. Paying the Toll: Local Power, Regional Politics and the Golden Gate Bridge, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

G. Ross Stephens and Nelson Wikstrom. 2000. Metropolitan Government and Governance: Theoretical Perspectives, Empirical Analysis, and the Future, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Annmarie Hauck Walsh. 1978. The Public’s Business: the Politics and Practices of Government Corporation, Cambridge: MIT Press.