From almost every angle, immigration generates interest and controversy. Scholars, pundits and policymakers regularly debate immigration and its effects: on culture, on jobs, on schooling. In particular, both academic and popular commentators have focused on whether immigration is associated with increases in unemployment, use of public benefits, or crime. Examinations of these questions have generally revealed that immigration has no effect, or that the effect, if present, is small. Even in the heated debate about immigration and employment, which receives the most popular attention, academics on both sides agree that the effects, be they negative or positive, are modest when compared to the economy as a whole.

Less attention has been paid to an area where immigrants do have a substantial impact: public transportation. Immigrants comprise a large and growing segment of the population, and are twice as likely as native-born workers to commute by public transit. In California, for example, immigrants comprise just over a quarter of the population (27 percent), but more than half of all transit commuters.

Immigrants comprise a large and growing segment of the population, and are twice as likely as native-born workers to commute by public transit.

Immigration has contributed significantly to transit ridership in California, and has been responsible for almost all ridership growth since the 1980s; without immigration, transit use in the state would have declined. This ridership gravy train, however, is unlikely to last. The longer immigrants stay in the country, the less likely they are to use transit, and the number of new immigrants is projected to fall. One way transit agencies can address the potential loss of immigrant riders is to better meet the needs of those (fewer) immigrants who will be newly-arriving—perhaps by enhancing transit services in the dense urban neighborhoods that continue to serve as immigrant ports of entry. In what follows we discuss the role that immigrants play in transit ridership, why immigrants have that role, and how that role is likely to change. We focus on California, because California has long had more immigrants than any other state and therefore provides a useful illustration of the dynamics we describe. Because reliable data on transit use by nativity are only available for the journey to work, we analyze transit commutes and use this as a proxy—albeit an imperfect one—for overall transit ridership.

Immigrant Transit Use

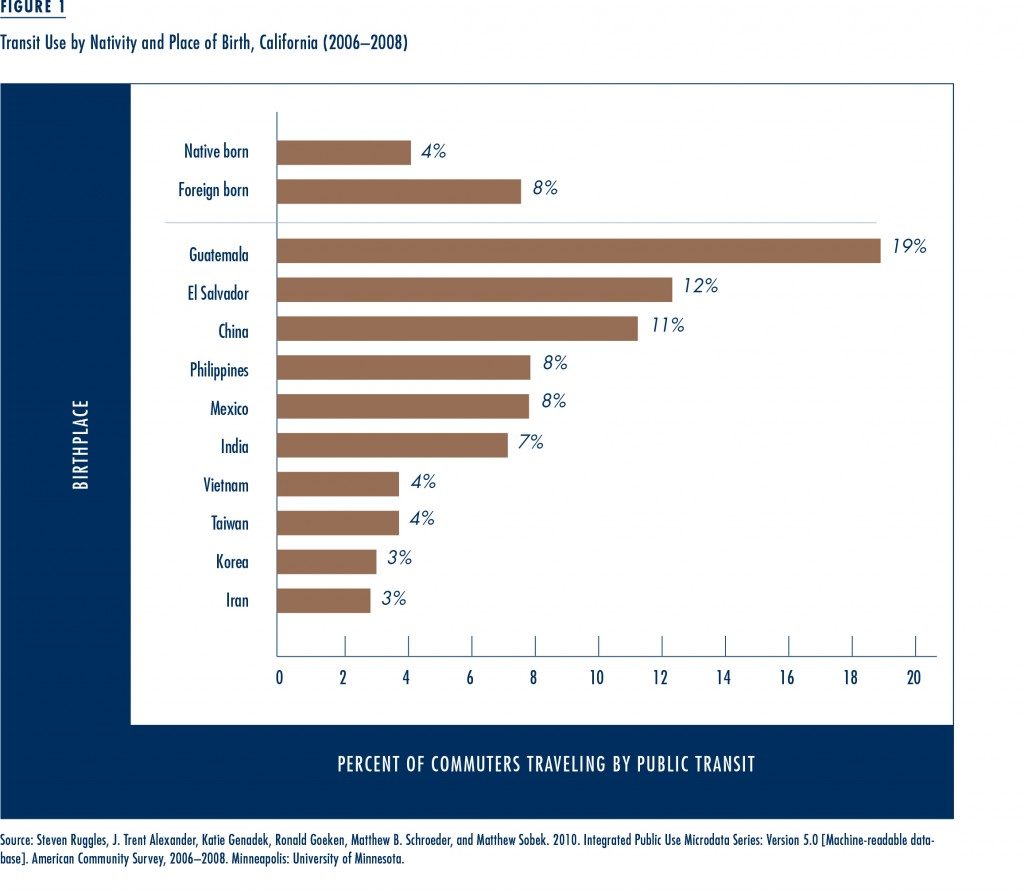

The fact that immigrants use transit much more than the native born does not mean that most immigrants use transit; it means very few native born do. Most immigrants, like most other American commuters, travel to work by automobile. In 2006–08, almost 90 percent of California’s foreign-born population traveled to work by private vehicle, and only 8 percent by public transit. Nevertheless, as Figure 1 shows, immigrants in California commute by public transit at rates twice that of native-born workers. Immigrants are not a monolithic group, however, and there are substantial differences in public transit commuting across immigrant groups and urban areas. The ten immigrant groups listed in Figure 1 represent 78 percent of the foreign-born workers in California, and their transit usage rates vary widely. For example, almost a fifth of Guatemalan immigrants commute by public transit, compared to only three percent of immigrants from Korea and Iran, who use transit less frequently than native-born workers.

Immigrant transit use can be explained by a number of factors. Immigrants are more likely than native-born workers to have lower incomes, and therefore less likely to be able to afford automobiles. Further, many immigrants—at least initially—settle in large urban areas where high population densities make transit service feasible and convenient. And a number of immigrants settle in ethnic enclaves, residential neighborhoods where local businesses, services, and institutions cater to the needs of co-ethnics (Chinatowns are a classic example). These neighborhoods are often quite dense, and driving in them is inconvenient for anyone, immigrant or non-immigrant. But immigrants might be more likely to make most of their trips in that neighborhood, as a result of ethnic attachment. Where a native-born resident might take advantage of car-friendly alternatives nearby, immigrants might run more of their errands and arrange more of their daily activities within the dense enclave, and as a result be less likely to drive and more likely to take public transportation. Cultural and legal factors also may help explain immigrant transit use. Many immigrants arrive in the U.S. from countries where automobile ownership is extremely low and transit use is high. Immigrants’ lack of driving experience and prior familiarity with transit may help to explain their continued use of transit in the U.S. Moreover, some immigrants want to drive but are legally prohibited from doing so. In California and many other states, people must show proof of legal presence in the U.S. to obtain a driver’s license. Therefore, undocumented workers—who constitute approximately 9 percent of California’s labor force—are not legally eligible to drive.

Immigrant transit use can be explained by a number of factors. Immigrants are more likely than native-born workers to have lower incomes, and therefore less likely to be able to afford automobiles. Further, many immigrants—at least initially—settle in large urban areas where high population densities make transit service feasible and convenient. And a number of immigrants settle in ethnic enclaves, residential neighborhoods where local businesses, services, and institutions cater to the needs of co-ethnics (Chinatowns are a classic example). These neighborhoods are often quite dense, and driving in them is inconvenient for anyone, immigrant or non-immigrant. But immigrants might be more likely to make most of their trips in that neighborhood, as a result of ethnic attachment. Where a native-born resident might take advantage of car-friendly alternatives nearby, immigrants might run more of their errands and arrange more of their daily activities within the dense enclave, and as a result be less likely to drive and more likely to take public transportation. Cultural and legal factors also may help explain immigrant transit use. Many immigrants arrive in the U.S. from countries where automobile ownership is extremely low and transit use is high. Immigrants’ lack of driving experience and prior familiarity with transit may help to explain their continued use of transit in the U.S. Moreover, some immigrants want to drive but are legally prohibited from doing so. In California and many other states, people must show proof of legal presence in the U.S. to obtain a driver’s license. Therefore, undocumented workers—who constitute approximately 9 percent of California’s labor force—are not legally eligible to drive.

Transportation Assimilation

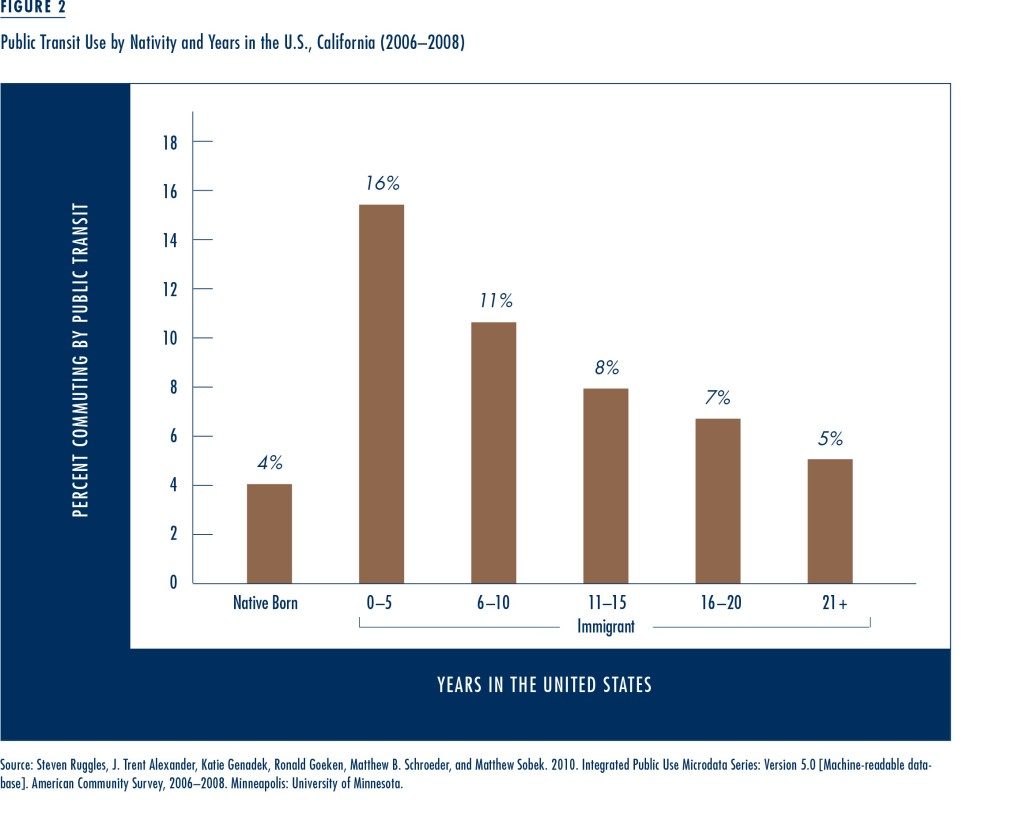

Over time, immigrants behave more and more like the native born, and transportation is no exception to this trend. Immigrants who arrive as transit users often graduate to cars. But automobiles are expensive to buy and operate, and ownership is only possible when households have the incomes necessary to manage these costs. Recent immigrants (i.e., those in the U.S. less than six years) have incomes substantially lower than more established immigrants and, as Figure 2 shows, they use transit the most. Sixteen percent of recent immigrants commute by public transit, a rate four times that of native-born commuters, and over three times that of immigrants who have been in the country over 20 years.

As immigrants assimilate economically, they gradually assume the auto-oriented travel patterns of the native-born. Transit use among immigrants steadily declines the longer they are in the country, and after more than 20 years in the U.S. immigrants commute by public transit at roughly the same rate as the native-born workers. Among the major racial and ethnic groups, Hispanic immigrants experience the greatest decline in transit use over time; however, their public transit use initially is so high (26 percent) that even after 20 years they remain more likely to use public transit (6 percent) than both other immigrant groups and the native born.

As immigrants assimilate economically, they gradually assume the auto-oriented travel patterns of the native-born. Transit use among immigrants steadily declines the longer they are in the country, and after more than 20 years in the U.S. immigrants commute by public transit at roughly the same rate as the native-born workers. Among the major racial and ethnic groups, Hispanic immigrants experience the greatest decline in transit use over time; however, their public transit use initially is so high (26 percent) that even after 20 years they remain more likely to use public transit (6 percent) than both other immigrant groups and the native born.

Income alone is not responsible for immigrants’ migration away from transit over time. In general, economic assimilation enables, and occurs in conjunction with, spatial assimilation, which further motivates a shift from public transit to driving. Many immigrants initially settle in ethnic enclaves, because the residents of the enclaves can help new arrivals adjust to life in the United States by providing assistance with accommodations, employment, and other services. Historically, these ethnic neighborhoods have emerged in dense central cities where transit is cost-effective and convenient. Over time, however, many immigrants become more affluent and relocate to the suburbs. In California, 41 percent of recent immigrants live in the central city, compared to only 32 percent of immigrants who have lived in the U.S. more than 20 years. Transit service in the suburbs is often limited and travel distances are frequently long, making cars a more desirable mode of travel.

Ethnic neighborhoods have emerged in dense central cities where transit is cost-effective and convenient.

Finally, regardless of whether they live in a suburb or a central city, a growing percentage of immigrants have moved, both in California and nationally, to regions that are less urban. In 1988, almost half (47 percent) of legal immigrants to California stated that they would settle in Los Angeles (39 percent) or San Francisco (8 percent). By 2008, however, this figure had fallen to 36 percent—with 32 percent planning to live in Los Angeles and 4 percent in San Francisco. Over this same time period, immigrants flooded into outlying low-density counties such as Riverside and San Bernardino—counties that experienced rapid population growth in general. Between 1988 and 2008, Riverside and San Bernardino increased the size of their immigrant populations by a whopping 560 and 315 percent, respectively. Yet transit service in these metropolitan areas is far less extensive than in Los Angeles or San Francisco, and immigrants who move to these outlying regions are more likely to be dependent on cars.

Immigrant Assimilation and Transit Commuting

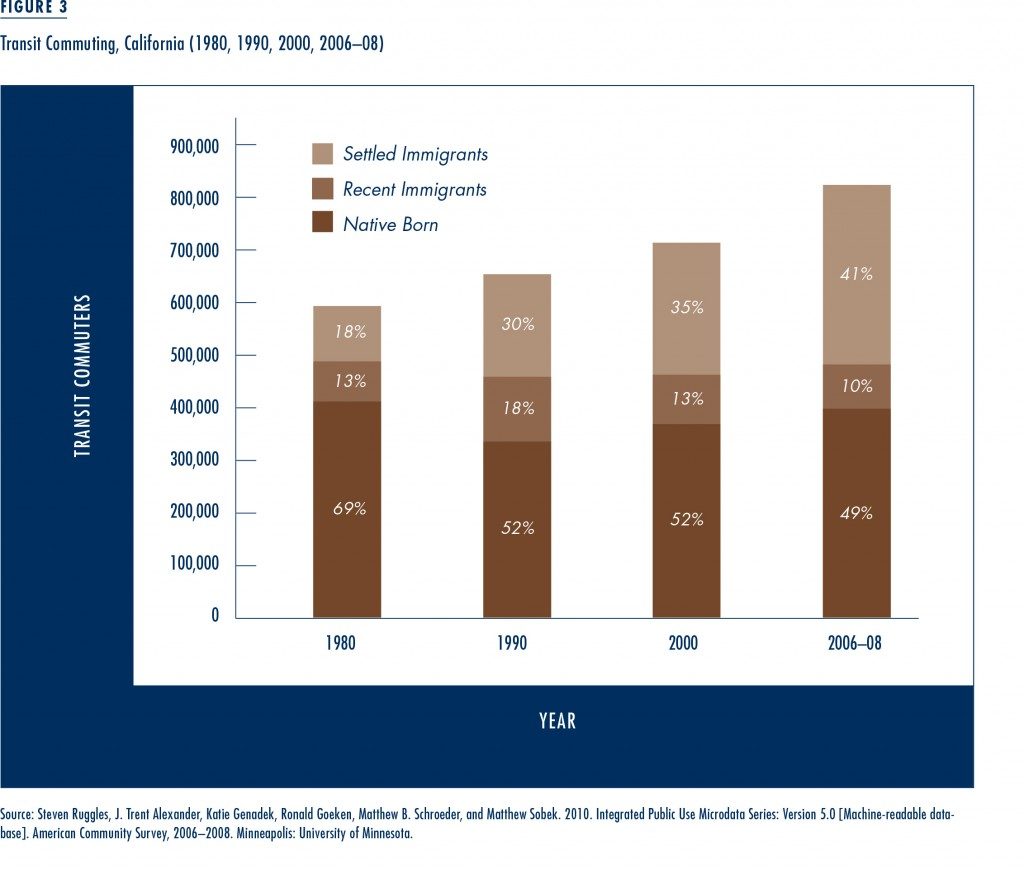

Cumulatively, the trends we discuss above have affected the size and composition of public transit commuters in California. Figure 3 uses Census data from 1980, 1990, 2000, and 2006–08 to show changes in the number and composition of transit commuters. To distinguish the contribution of recent immigrants from more established immigrants, immigrants are categorized as follows: immigrants who at the time of the survey had lived in the U.S. for less than six years, and more settled immigrants who had lived in the U.S. for six years or more. Between 1980 and 2006–08, the number of transit commuters in California grew by over 200,000 people, an increase of almost 40 percent. Yet this increase was driven almost entirely by immigration. Despite dramatic increases in public transit investment over this period, the number of native-born transit commuters remains slightly below 1980 levels.

Immigrants, who accounted for 30 percent of all transit commuters in 1980, represented 51 percent of all transit commuters by 2006–08. Among these immigrant transit commuters, the majority are Hispanic (65 percent) and the remainder Asian (25 percent), White (7 percent) and Black (2 percent). In some California metropolitan areas, the percentage of immigrant transit commuters is substantially higher than the state average. Immigrants in the Los Angeles metropolitan area, for example, account for less than half of all workers, but more than two-thirds (67%) of all transit commuters.

Immigrants, who accounted for 30 percent of all transit commuters in 1980, represented 51 percent of all transit commuters by 2006–08. Among these immigrant transit commuters, the majority are Hispanic (65 percent) and the remainder Asian (25 percent), White (7 percent) and Black (2 percent). In some California metropolitan areas, the percentage of immigrant transit commuters is substantially higher than the state average. Immigrants in the Los Angeles metropolitan area, for example, account for less than half of all workers, but more than two-thirds (67%) of all transit commuters.

In some California metropolitan areas, the percentage of immigrant transit commuters is substantially higher than the state average.

Note, however, that immigrants’ propensity to use transit did not rise. Quite the opposite—the share of immigrants using transit fell from 11 percent in 1980 to 8 percent in 2006–08. So the increased immigrant share of overall transit ridership was due entirely to the substantial growth in the immigrant population. But the number of new immigrants has fallen steadily since 1990. This decline in immigration has large implications for the future of transit ridership in California. The largest growth in immigrant transit commuting—a 70 percent increase—occurred during the 1980s, when immigration to both the U.S. and California rose rapidly. Immigration peaked in 1991, however, when almost 2 million legal immigrants and refugees entered the U.S. In the subsequent decade both immigration growth and the growth in immigrant transit commuters slowed—the number of immigrant transit commuters increased modestly by 12 percent.

In the absence of immigrants, the number of transit commuters in California would be less than half what it is today. The future of public transit ridership in California therefore rests in large part on how many immigrants we will have, and how these immigrants will choose to travel. Most evidence suggests that in the near future we will have fewer immigrants, and those immigrants will tend to drive. Immigration to the United States is slowing, dampened by increased border enforcement and the recent recession. So too has immigration to California. From 2002 to 2009, legal immigration to the state fell by 21 percent. The decline was more than twice as rapid among immigrants from Mexico and Central America (45 percent), the population groups that are most likely to use public transit. Moreover, unauthorized immigration to California—much of it from Mexico—seems to be at a standstill. Therefore, those immigrants who do arrive, and those already here, will probably continue to assimilate to automobile use, a trend that is likely to accelerate with the growing use of automobiles worldwide.

Growing the Market for Public Transit

Forecasting the future is difficult, particularly since immigration is influenced by federal policy that is subject to change. However, trends in immigration, immigrant transit use, and immigrant residential location suggest that transit agencies in California and other traditional immigrant ports of entry ought to be concerned about their ridership. All signs point to the foreign-born population—a historically dependable transit market—growing at a slower pace and continuing to assimilate to automobiles.

Transit agencies must either find ways to retain immigrant riders or fill the ridership gap with other markets. In the last ten years, transit researchers have recognized the importance not only of attracting new choice riders, but also of retaining existing riders. In fact, retaining existing riders may well be a more cost effective strategy for maintaining transit ridership levels. Given the high percentage of immigrants who have first-hand experience using public transit, immigrants ought to be an important group around which transit agencies target their retention efforts.

Some transit agencies already have adopted strategies to better serve immigrant riders; however, the effects of these programs are unknown. For example, many transit agencies provide information in multiple languages to improve the transit experience of linguistically-isolated riders. While important, language services should be only one component of much larger efforts to improve transit services for immigrants. Focus groups with immigrant transit users show that their needs are similar to those of native-born transit riders; they want service that goes to more places at more times, more frequent service, easier transfers, and they want to feel safe and comfortable both while riding transit vehicles and while waiting for them to arrive. To better capture the immigrant market and potentially slow immigrants’ assimilation to cars, transit service enhancements could be targeted to immigrant ports of entry. Another promising approach—one that already has emerged—emphasizes alternatives to traditional fixed-route, fixed-schedule transit service. Such alternatives include a range of both formal and informal services such as taxis, vanpools, minibuses, jitneys, demand-responsive vans, station cars and bicycles, and limited route-deviation bus service—options that already are provided in some communities.

To retain their most reliable customers, transit managers must understand the dynamics of immigrant travel behavior and the transit needs of their immigrant ridership.

Immigrants are an important and, in some places, the most important segment of the public transit market. Immigrant reliance on transit, however, is a particularly disquieting trend for transit managers in places where immigration is slowing, such as Los Angeles, New York and Chicago. Transit agencies must plan for these changes. To retain their most reliable customers, transit managers must understand the dynamics of immigrant travel behavior and the transit needs of their immigrant ridership. In states such as California, failure to do so—holding all other trends constant—will have grave consequences for the future of public transit.

Further Readings

Blumenberg, Evelyn and Alexandra Elizabeth Evans. 2010. “Planning for Demographic Diversity: The Case of Immigrants and Public Transit,” Journal of Public Transportation, 13(2): 23-45.

Steven Ruggles, J. Trent Alexander, Katie Genadek, Ronald Goeken, Matthew B. Schroeder, and Matthew Sobek. 2010. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 5.0 [Machine-readable database].