Almost everyone can tell an anecdote about disabled placard abuse. One of mine stems from a visit to the Capitol building in Sacramento. After noticing that cars with disabled placards occupied almost all the metered curb spaces surrounding the Capitol, I talked to one of the state troopers guarding a driveway entrance. He watched all the arrivals and departures at the nearby metered spaces every day. When I asked the trooper to estimate how many of the placards he thought were being used illegally, he responded, “All of them.”

Newspapers often report placard abuse, such as the scandal that occurred when 22 UCLA football players were found to be using disabled placards to park on campus; the athletes got their placards by forging doctors’ signatures for such conditions as asthma and palsy. UCLA seems to be unusual only in the large number of athletes who were caught misusing disabled placards, because similar scandals have erupted on other campuses. In 2003, the quarterback at Florida State University earned national attention for repeatedly parking illegally in spaces reserved for the disabled. Placard abuse is common enough to have its own website, handicappedfraud.org.

Treating disabled placards as free parking passes has encouraged widespread abuse by able-bodied drivers who simply want to park wherever they want, whenever they want, without paying anything.

Making curb parking accessible to people with disabilities is a laudable goal, but treating disabled placards as free parking passes has encouraged widespread abuse by able-bodied drivers who simply want to park wherever they want, whenever they want, without paying anything. Because of the widespread abuse, disabled placards do not guarantee a physical disability. Instead, they often signal a desire to park free and a willingness to cheat the system. Placard abusers learn to live without their scruples, but not without their cars.

Anecdotes and newspaper reports are not hard evidence, but if placard abuse were rare, one would expect to find some studies that report little abuse. I have never seen one. Instead, I have seen several careful studies that show widespread abuse. A survey in downtown Los Angeles shows how extensive the abuse can be. A research team from UCLA observed a block with 14 parking meters for a full day, and most of the curb spaces were occupied most of the time by cars with disabled placards. For five hours of the day, cars with placards occupied all 14 spaces. The meter rate was $4 an hour, but the meters earned an average of only 32¢ an hour. Cars parked free with placards consumed $477 worth of meter time during the day, or 81 percent of the potential meter revenue on this block. Several drivers with disabled placards were observed carrying heavy loads between their cars and the adjacent businesses.

Placard abusers steal revenue from cities, and drivers with real physical disabilities have a harder time finding curb spaces, which are usually the most convenient spots for people with disabilities to park. When all the curb spaces near their destinations are occupied, drivers who have difficulty walking may have to park much farther away or even abandon their trips.

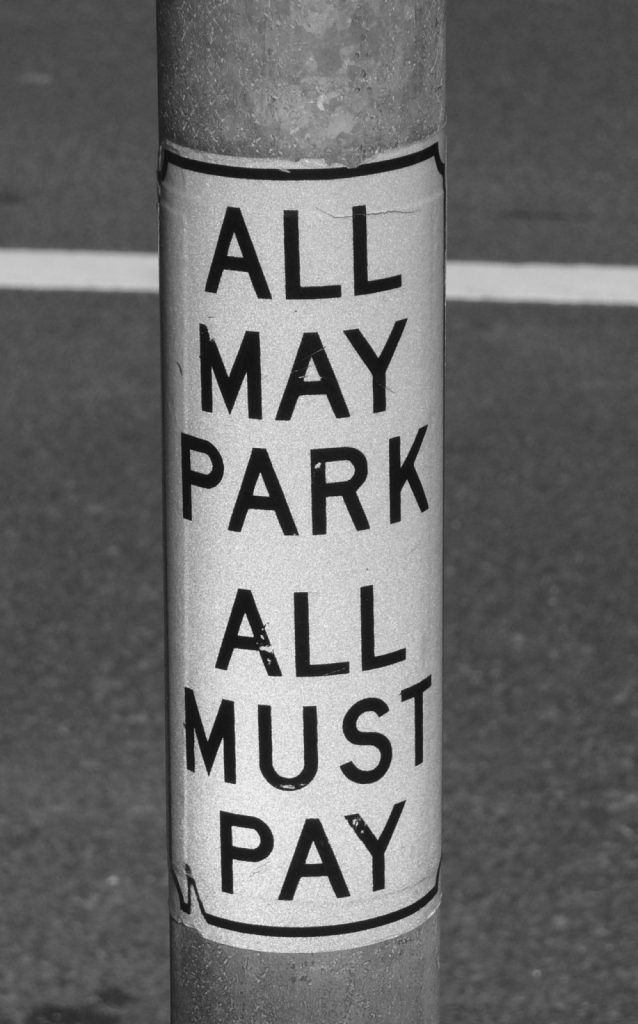

If a state exempts all cars with placards from paying at meters, how can cities prevent placard abuse and preserve disabled access? Virginia has a sensible policy. It exempts drivers with disabled placards from paying at meters, but it also allows cities to set aside this exemption if they give reasonable notice that payment is required. In 1998, Arlington removed the exemption for placards and posted “All May Park, All Must Pay” on every meter pole. Because it is easier to pull into and out of the end space on a block, Arlington puts meters reserved for drivers with disabilities at many of these end spaces. The purpose is to provide parking in convenient locations for people with disabilities, not to offer a subsidy that invites gross abuse. Cities can reserve the most accessible meter spaces for disabled placard holders, but accessible is not the same as free.

If a state exempts all cars with placards from paying at meters, how can cities prevent placard abuse and preserve disabled access? Virginia has a sensible policy. It exempts drivers with disabled placards from paying at meters, but it also allows cities to set aside this exemption if they give reasonable notice that payment is required. In 1998, Arlington removed the exemption for placards and posted “All May Park, All Must Pay” on every meter pole. Because it is easier to pull into and out of the end space on a block, Arlington puts meters reserved for drivers with disabilities at many of these end spaces. The purpose is to provide parking in convenient locations for people with disabilities, not to offer a subsidy that invites gross abuse. Cities can reserve the most accessible meter spaces for disabled placard holders, but accessible is not the same as free.

The purpose is to provide parking in convenient locations for people with disabilities, not to offer a subsidy that invites gross abuse.

A neighboring city, Alexandria, is considering a similar opt-out policy as part of a broader strategy to manage on-street parking and reduce placard abuse. To gauge the seriousness of abuse, the Alexandria Police Department interviewed drivers who were returning to cars displaying disabled placards and found that 90 percent of the placards checked were being used illegally.

Because parking with placards seems to be an almost ethics-free zone, cities should aim to avoid creating financial incentives to abuse any placard policy. Raleigh, North Carolina, for example, allows drivers with disabled placards to park for an unlimited time at meters, but requires them to pay for all the time they use. Placard users push a button on the meter allowing them to pay for time beyond the normal limit for other drivers, and enforcement officers can then check to see whether the cars using this privilege display a placard.

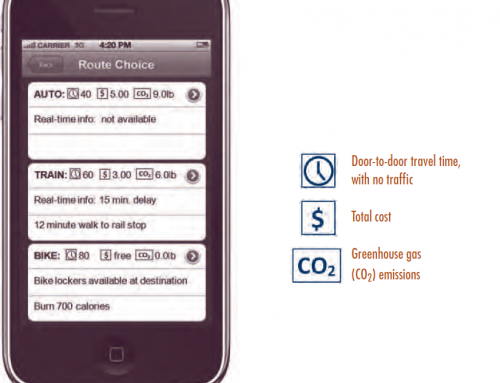

If people with disabilities must pay at meters, their difficulty in getting to and from the meters may be a barrier, especially at pay-and-display meters. If it is raining or snowing, the barrier will be even greater. To solve this problem, some cities offer placard holders the option to pay with in-vehicle meters or by cell phone. Offering these options can forestall objections that the payment method is itself an obstacle to people with disabilities.

Ending free parking for placard users will bring in new revenue that can pay for services benefiting all people with disabilities, not just drivers with placards. If a city proposes to end free parking for cars with placards, it can estimate the meter revenue currently lost because of placard use and commit all the new meter revenue to pay for specialized transportation services for everyone with disabilities.

If a city proposes to end free parking for cars with placards, it can estimate the meter revenue currently lost because of placard use and commit all the new meter revenue to pay for specialized transportation services for everyone with disabilities.

The data from Alexandria illustrate how an all-must-pay policy can benefit the disabled community. The police survey found that placard abuse accounts for 90 percent of the revenue lost from the placard exemption. Alexandria also estimated that an all-must-pay policy will yield $133,000 a year in new meter revenue currently lost to the placard exemption. If placard abusers account for 90 percent of this lost revenue, they misappropriate $120,000 of the subsidy intended for people with disabilities, while people with disabilities receive only $13,000. Spending the full subsidy to provide paratransit services or taxi vouchers for everyone with disabilities seems much fairer than wasting 90 percent of it to provide free parking for able-bodied placard abusers. The transportation subsidy for the disabled community will increase by 10 times, at no additional cost to the city government. Because almost all the additional spending will come at the expense of disabled placard abusers, it is easy to see why Alexandria is considering a shift to Arlington’s all-must-pay policy, while Arlington is not considering a return to the all-placards-park-free policy.

Beyond raising revenue to finance new transportation services for everyone with disabilities, the all-must-pay policy can also eliminate the culture of corruption that has grown up around using disabled parking placards as free parking passes. Cities and states encourage this corruption by making it so easy, so profitable, and so rarely punished. Because enforcement is difficult, the chance of getting a ticket for placard abuse is so low that even high fines do not prevent violations.

Cities and states encourage this corruption by making it so easy, so profitable, and so rarely punished.

Charging all drivers for parking at meters and spending the new revenue to provide transportation for the entire disabled community can improve life for almost everyone—except the drivers who now abuse disabled parking placards.

Further Readings

Donald Shoup. 2011. The High Cost of Free Parking, Chicago: Planners Press.